A nationally-known First Amendment attorney calls state Rep. Renny Cushing’s attempt to blackball the news site New Hampshire Journal “absolutely outrageous,” part of a chorus of concerns raised by the top House Democrat’s actions.

Cushing, who is the Minority Leader in the House of Representatives, released a public letter last week telling fellow Democrats in his caucus “PLEASE, DO NOT TALK TO NH JOURNAL.” He took the action in response to weeks of reporting by NHJournal on dissent within his caucus over accusations of racism and antisemitism among its members.

In an open letter of response, NHJournal noted that in 2011, GOP Speaker of the House Bill O’Brien barred Concord Monitor reporter Annamarie Timmins from a press event in his office. Media outlets like the Union Leader and Concord Monitor responded at the time by calling his actions “dictatorial” and “ill-advised.”

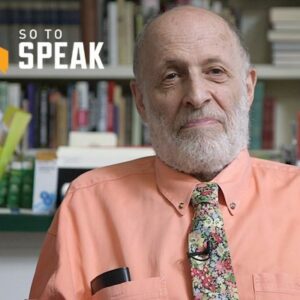

Harvey Silverglate, a First Amendment attorney based in Cambridge, Mass., had similar criticisms for Cushing today.

“I think it’s absolutely outrageous for a public official to take a position that he will not speak with a press outlet, merely because he doesn’t like what the reporter writes,” Silverglate said. “It’s fine for a private citizen to boycott a particular reporter or media outlet, but not for a public official to do so. And it doesn’t matter if the political figure trusts the newspaper. The fact is that public officials have myriad ways of communicating with their constituents. If they feel that newspaper or radio or TV station number one is unfair, they can give an interview to a friendlier outlet.

Silverglate is a co-founder of the free speech organization the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) and, until recently, a member of the board of the Massachusetts ACLU.

“Public officials are not private citizens. When they get elected to public office, their primary loyalty remains to the public, to their constituents, not to their own careers,” Silverglate added.

Tim Graham, director of media analysis for the Media Research Center, a media watchdog organization, responded to the report of Cushing’s move by noting, “Saying ‘Don’t engage with media that’s out to harm us’ would be called anti-First Amendment if the parties and media were reversed.”

Local organizations, such as the New Hampshire Press Association, the New England Press Association, and the ACLU-NH have all declined to make a statement on Cushing’s actions or the press freedom issues it raises.

“It’s a tough call,” NHPA’s president Brendan McQuaid told NHJournal. “Seems like your free speech rights are the same as Rep. Cushing is using in this case.”

And UNH law professor Albert “Buzz” Scherr told NHJournal that, from a legal standpoint, “it’s fine if politicians want to exclude members of the media. There’s no ‘reverse First Amendment’ that requires them to talk to reporters, even though they’re public officials.

“This is part of the delightful hurly-burly of public life,” Sherr said.

For Scherr, the issue is less about some abstract principle of press freedom and more about the realities of politics as it’s practiced.

“And as my mother said, ‘other than baseball, politics is the best spectator sport.”

Silverglate doesn’t agree, and he’s disappointed that would-be allies of the First Amendment are remaining silent.

“It’s outrageous that the ACLU-NH won’t stick up for free speech with which its progressive leaders disagree. They are taking their cue from the national organization,” Silverglate said.

However, Timmins — who now writes for the left-leaning New Hamsphire Bulletin — did offer a comment via Twitter on Monday.

“Banning me from his press conferences and office didn’t stop our @ConMonitorNews coverage of former Speaker Bill O’Brien. Safe to say it won’t stop @NewHampJournal either. There are more productive ways to mend media disagreements, even a fierce one.”