Pollsters were heavily criticized after the presidential election for completely missing the mark on their predictions. Across the country, they were scratching their heads, trying to figure out how they didn’t see Republican Donald Trump defeating Democratic challenger Hillary Clinton.

Even the University of New Hampshire Survey Center had to take a step back and figure out what went wrong for them. In their last Granite State Poll before the November election, they predicted an 11-point victory for Clinton. She actually won New Hampshire by four-tenths of a percentage point, 47.6 to 47.2 percent.

Their last survey also had Democrat Colin Van Ostern beating Republican Chris Sununu by 11 percent, 55 to 44 percent, for the governor’s office. Sununu beat Van Ostern by 2 percent.

For many political strategists in the state, these way-off predictions confirmed their suspicions that the UNH survey is a “bad poll.” Even WikiLeaks exposed that the Clinton campaign didn’t think much of them.

“As always, this poll doesn’t have a good history of accuracy so we need to take it with a grain of salt,” Clinton campaign manager Robby Mook wrote to Clinton about a recent UNH pre-primary poll May 5, 2015.

“The state of survey research is not static and there are a lot of technological changes and problems,” said UNH Survey Center director Andrew Smith. “We do an analysis after each election to look for biases that come into the surveys.”

Smith said he believes he found the reason why his numbers were so off during the election and he tweaked his methodology to reflect that in his most recent UNH poll released this week.

In his past polls, he would weight the sample based on age, sex, and region of the state, in addition to the number of adults and telephone lines within households. Often pollsters will weight their samples to adjust for oversampling and undersampling of key demographics. For example, more women than men, and more older people than younger people, answer polls in the Granite State, Smith said.

Now, Smith added level of education into the mix.

“It’s a difficult variable to use and in the past it didn’t have that much political correlation when we used it, so it didn’t make a difference statistically,” he told NH Journal. “However, we saw that in this election, the percentage of people with a college education make a significant difference, and had we weighted it going into the election, we would have been dead accurate on all of the results.”

This election showed that Trump won the support of white, blue collar workers with some college education or less. He also over-performed in rural areas, while Clinton did better in more wealthy suburban areas.

Smith said he found that men with some college education, known as the Trump coalition, were not participating in the UNH surveys as much as they did when it came time to vote.

“It’s a new phenomena in New Hampshire politics,” he said. “Is it due to Trump? Probably, but it certainly made a difference in our polls. Hopefully, our methods are improved.”

The UNH Survey Center released four polls since February 10. The first one, released last Friday, was on Trump’s approval ratings in the Granite State, which found that residents are pretty divided on the president.

Forty-three percent of adults said they approve of the job Trump is doing as president, while 48 percent are disapproving of his performance, and 8 percent are neutral, the poll found.

These numbers are close to the national trend. The Pew Research Center released Thursday the findings of its survey, which found 39 percent approve of his job performance, while 56 percent disapprove.

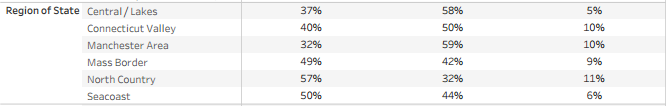

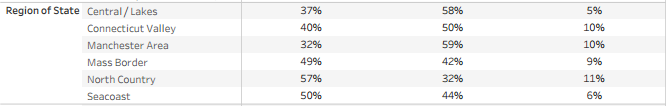

Looking at the different regions of the state, his approval rating also varies. This is where it will be interesting to keep an eye on the UNH Survey Center to see if their new weighting of education level has an impact on the data.

In the Central/Lakes, Connecticut Valley, and Manchester area, his approval ranges from 32 to 39 percent. Along the Massachusetts border, on the Seacoast, and in the North Country, his approval rating is more positive.

Credit: UNH Survey Center

“It’s not surprising anymore,” Smith said. “Democratic political strength in the central part of the state and Connecticut River Valley is still there and Republicans have been strong in Massachusetts border towns and somewhat strong in the Greater Manchester area, like in Bedford.”

Smith said he found the political dynamics of the North Country interesting because that area is becoming more Republican. For years, it used to be an area of Democratic strength due to blue collar support for Democrats with union support.

“The character and self-identification of the people in the North Country is different than the rest of the state,” he said. “They have not been doing well economically and the Democratic Party has been having difficulty holding onto these blue collar people.”

As exhibited by Trump’s win, many of these blue collar workers in New Hampshire, and in other states across the country, lent their support to the president.

“All we are seeing right now is a group of people who are quasi-Republicans, who might not have participated in politics before, or turned out greater in number, but we’ll have to see how that plays out in the next several years,” Smith said.

The other polls released this week showed that the drug crisis is still the number one issue for residents in the state, Gov. Sununu has similar approval ratings at the start of his term as his predecessors, and all of New Hampshire’s congressional delegation have positive approval ratings.

Follow Kyle on Twitter.