NH Supreme Court Stays ConVal Education Spending Ruling

New Hampshire taxpayers don’t have to pay a $537 million education spending bill just yet, as the New Hampshire Supreme Court stayed the decision in the ConVal lawsuit.

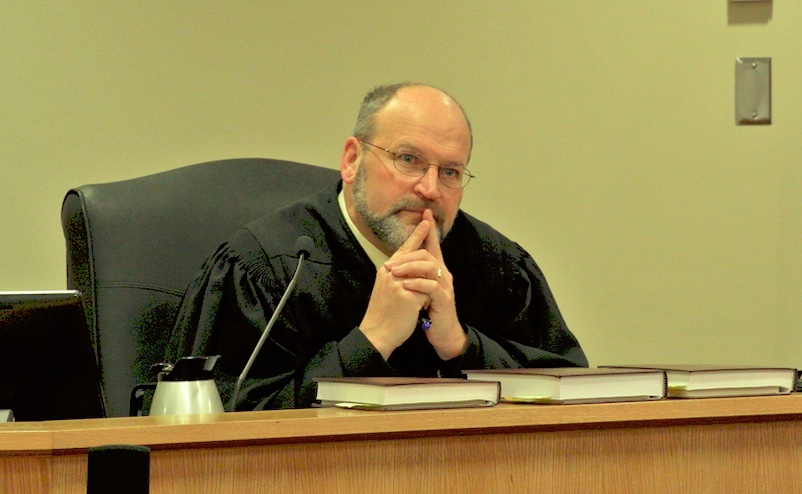

In a unanimous decision issued Wednesday, the Supreme Court put a hold on Rockingham Superior Court Judge David Ruoff’s November order that the state’s per-pupil spending must go up to at least $7,300. Ruoff had denied a motion to stay his decision pending appeal earlier this year.

Gov. Chris Sununu praised the stay decision, saying Ruoff’s ruling went too far.

“Today, the Supreme Court rightfully paused an attempt by one judge to usurp the power and preferences of both the legislative and executive branches,” Sununu said. “Grateful for the Supreme Court’s action to stay a decision that was so clearly overreaching.”

According to Senate President Jeb Bradley (R-Wolfeboro), implementing Ruoff’s order would wreck state finances, hurt lower-income communities, and eventually force an income or sales tax on Granite Staters.

“This decision could mean a $500 million spending increase for New Hampshire taxpayers and could cause reduced education funding for all the original towns that brought the Claremont education funding lawsuit by limiting the legislature’s ability to target special education aid to local school districts that need it the most,” Bradley said in a statement. “I remain optimistic that the Supreme Court will recognize that such huge financial decisions rest with representatives and senators that the people of New Hampshire have chosen.”

Lawmakers are looking for an affordable funding solution, and according to House Speaker Sherman Packard (R-Londonderry), the Supreme Court’s stay will give both houses time to keep working.

“We’re hopeful the Supreme Court has a different take on the matter than the lower court that will be less costly to taxpayers. The stay will allow the legislature more time to further analyze the situation,” Packard said.

The Peterborough-based Contoocook Valley Regional School District filed the lawsuit in 2019, arguing that the state’s education grant of $3,600 per pupil was far below the true cost and, therefore, unconstitutional. ConVal and the dozens of school districts that joined the lawsuit wanted closer to $10,000 per pupil.

Ruoff originally refused to set a dollar amount when he ruled the state violated the constitutional right to an adequate education, leaving that up to lawmakers. But a subsequent appeal to the state Supreme Court resulted in a 2021 order that forced Ruoff to come up with a figure.

Since the ConVal lawsuit was filed, lawmakers and Sununu have bumped up the grants to $4,100 per pupil, an amount Ruoff still found unconstitutionally low. Ruoff’s decision acknowledged it is up to the legislature to determine the funding but that it can be no less than the amount he set.

“What is the base cost to provide the opportunity for an adequate education 239 years after that fundamental right was ratified in our constitution? The short answer is that the legislature should have the final word, but the base adequacy cost can be no less than $7,356.01 per pupil per year, and the true cost is likely much higher than that. At a minimum, this is an increase of $537,550,970.95 in base adequacy aid to New Hampshire Schools,” Ruoff wrote.

The legal tussle over New Hampshire’s state spending for education “adequacy” is unrelated to another hot-button political issue: Taxpayers are already burdened with increasing education costs even as the number of students is declining.

The total cost of education in New Hampshire, including the portion paid through local property taxes, averages more than $20,000 per pupil. That’s up from about $11,000 total per pupil spending in 2000. Over the same time, the state’s student population has fallen by more than 20 percent. According to the Department of Education, student enrollment numbers in the Granite State have dropped from 207,684 in 2002 to 165,095 in 2023. That’s a decrease of 42,589 public school students, or about a 20.5 percent decline during the past 21 years.