GOP Lawmakers Ask High Court to Dump Claremont Decisions

As the New Hampshire Supreme Court considers the $500 million ConVal education funding decision, GOP lawmakers have come up with a solution for the endless legal drama: Get rid of the Claremont decisions.

In an amicus brief filed with the court this week, a group of 31 House and Senate Republicans justify ending Claremont by linking it to the logic behind the Roe v. Wade decision that created a woman’s right to an abortion.

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe with the recent Dobbs decision, restoring the right of voters to set the abortion laws in their own states. Like Roe, they argue, Claremont was a bad decision that took authority away from local communities and created endless legal battles.

“In Dobbs, the U.S. Supreme Court acknowledged the morass into which it had ventured in 1973 and overruled Roe and Casey, returning the controversial policy issue of abortion to the policy-making branches of the 50 state governments,” the brief states.

The landmark state Supreme Court Claremont decisions from the 80s and 90s found that all New Hampshire children have a right to an “adequate education” and that the state has a financial obligation to fund that education.

State Sen. Tim Lang (R-Sanbornton) said the Claremont rulings have done more harm than good, taking away local control from communities and creating the legal environment for the costly ConVal decision.

“The decision has run its course and its not taking into account the entire state of New Hampshire,” Lang said.

But Noah Telerski, with the liberal NH School Funding Fairness Project, said the brief is an example of blame shifting by the GOP lawmakers.

“Instead of owning up to their failure to adequately fund education in compliance with the Claremont rulings, these legislators are instead arguing that Claremont should be thrown out,” Telerski said in a statement. “They are trying to blame the court for their own failure to comply with the court’s rulings over the past 30 years. And this begs the question, what do they think the state’s role in funding education should be?”

Lang, along with House Speaker Sherman Packard (R-Londonderry) and 29 other GOP lawmakers, signed on to the amicus brief, promoted partially by the fact the New Hampshire Department of Justice isn’t trying to overturn Claremont. The DOJ, in representing the state in the ConVal appeal, makes the error of not challenging Claremont, the brief states.

The DOJ is focusing on getting the ConVal decision overturned, but that leaves open the possibility for more lawsuits over school fusing down the line, the brief states.

“If this Court were to reverse the lower court order, it would soon enough be called upon to pass on the constitutionality of another school funding law, and another, and another, until the Court would be forced to confront the decision the amici are urging it to confront now,” the brief states.

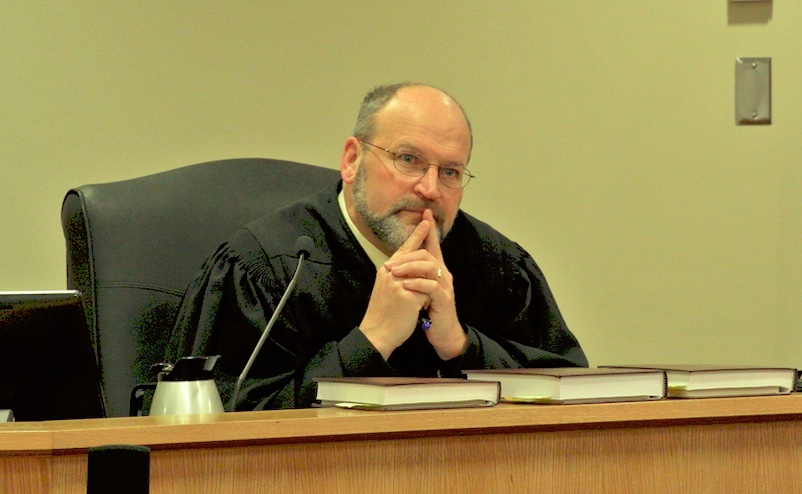

In the ConVal ruling, Rockingham Superior Court Judge David Ruoff sided with the Contoocook Valley Regional School District which argued the state’s per pupil adequacy grant of $4,100 was too low to provide the constitutionally guaranteed adequate education. Ruoff determined the grants should be a minimum of $7,300 per pupil for every pupil, representing an immediate $530 million spending increase.

Some lawmakers were horrified by the notion of a single judge arbitrarily creating a taxpayer-funded mandate, entirely outside the legislative process.

The $4,100 adequacy grants are average for most districts, but the legislature increases those grants for the poorest communities under the current system, Lanf said. Ruoff’s solution takes away the legislature’s ability to target school aid to poor communities like Claremont, he said.

“Towns like Claremont, towns like Berlin, would be devastated,” Lang said.