(This article first appeared at JBartlett.org)

It’s Teacher Appreciation Week, and Granite Staters are again being subjected to the claim that teachers here earn less than they should because legislators are stingy. Given current market conditions, average teacher pay in New Hampshire is lower than it should be to recruit the best candidates. But the state’s contribution isn’t the reason.

The National Education Association puts New Hampshire’s average teacher salary at $67,170, $4,860 below the national average (not accounting for cost of living or benefits).

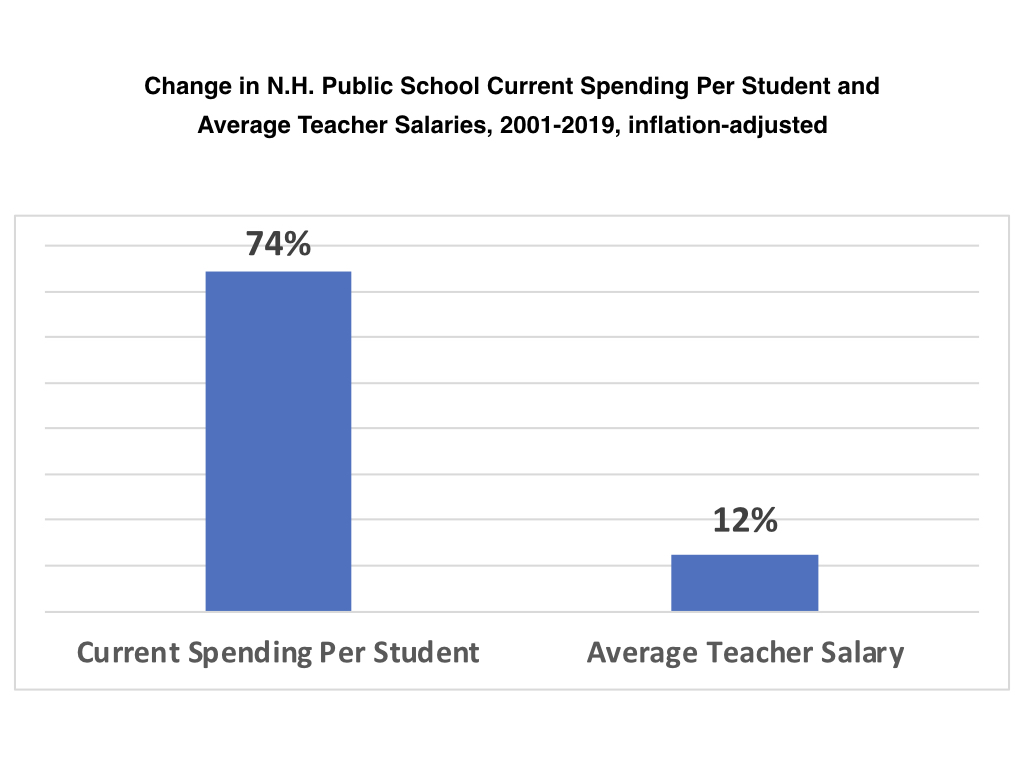

If we look at the two decades before the pandemic, total spending on district public schools in New Hampshire increased by 40 percent from 2001-2019, adjusted for inflation. Removing expenses such as capital and debt service, current spending per pupil rose by 74 percent, again adjusting for inflation.

That’s the kind of increase that should lead to large leaps in teacher pay. But it didn’t. Average teacher pay in New Hampshire from 2001-2019 rose by only 12 percent.

Where did the rest of that money go?

The largest chunk was spent on hiring staff, particularly non-teaching staff. From 1994-2022, New Hampshire district public schools had the nation’s largest increase in staffing relative to enrollment, as we reported here.

District K-12 public school staffing in New Hampshire increased by 55 percent from the 1994 to 2022 fiscal years, even as student enrollment fell by 11.2 percent. New Hampshire’s gap between staffing growth and enrollment—66.2 percentage points—was by far the largest margin among all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Seven states had larger percentage increases in staffing, but they all had large increases in enrollment as well, which produced smaller gaps between enrollment and staffing than New Hampshire’s.

We just have to look next door to Massachusetts to see how this preference for more staff can affect district budgets.

As of 2019 (before schools received any pandemic funding), New Hampshire public schools had 18.2 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff per 100 students vs. 13.9 per 100 students in Massachusetts public schools. For a school of 500 students, New Hampshire would have about 21.5 more FTE staff than a school of the same size in the Bay State.

Comparing New Hampshire to the national average as of 2019, a 500-student school in the Granite State would have 26 more FTE staff.

Despite large increases in total K-12 expenditures this century, even before COVID funding, districts have chosen to prioritize hiring, particularly in non-teaching positions, over instructor compensation.

New Hampshire schools are also staff-heavy on the instructional side. New Hampshire public schools employ more teachers per student than those in almost every other state. This also helps to suppress teacher pay.

The NEA’s own report shows that New Hampshire has the second lowest student-teacher ratio in the nation at 10.5 students per teacher. Vermont is lowest at 10.4. Massachusetts has 11.8 students per teacher, Maine 11.6, Connecticut 12.1, and Rhode Island 12.7. The national average is 15.1.

Looking at these numbers, the media missed probably the biggest story in the NEA’s report: New Hampshire employs 44 percent more teachers per student than the national average.

With 4.6 more teachers per student, New Hampshire public schools spread their labor costs among many more teachers. That benefits teachers unions, which have more dues-paying members per school. But it leaves less money for each teacher.

Though teacher pay in New Hampshire has risen in the last decade, including through the pandemic years, inflation has consumed the value of those raises.

According to the NEA’s report, from 2014-15 school year to 2024-25 school year the number of teachers fell by 4.8 percent while enrollment fell by 11.4 percent. In that time, teacher pay rose by 24 percent.

Again we see that enrollment declines far outpace staffing reductions. Maintaining high staffing levels can eat into pay rates. We also see that New Hampshire teacher pay raises, on average, have not kept up with inflation, though overall revenue for public schools has surpassed inflation this century.

All of these data points indicate that school districts have received enough revenue to fund more generous teacher pay increases, but they’ve prioritized higher staffing levels instead.