States are inching closer to implementing their own education plans that fall in line with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). In a bipartisan manner, Congress got rid of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2015 and rolled back some of the federal government’s control over education policy, giving states more power to set their own goals and increase accountability.

In New Hampshire, state officials released their ESSA draft plan in May and accepted public comments until Friday. The draft version of the Granite State’s plan stresses competency-based tests over standardized assessments, and vocational education tied to industry needs. ESSA doesn’t change how often schools must give out standardized tests. It is still required that testing occurs in third through eighth grades and once in high school, but the law gives states flexibility in deciding what schools need to report, what their goals are, and what criteria determines if a school is struggling or not.

For example, New Hampshire school districts still need to report their high school graduation rates and the test scores of annual standardized assessments. Those school districts participating in the state’s pilot PACE program don’t take standardized tests every year, but use locally-designed assessments. If the federal government renews the state’s waiver, that program will continue.

However, under the state’s ESSA plan, schools would also be assessed based on new metrics, including progress toward English language proficiency and how well the average student is progressing from year to year at the elementary and middle school levels. Another indicator would also track how well the lowest-performing students are progressing each year.

High schools will also measure and report on college and career readiness. Schools will be scored on how many students fulfill at least two of nine requirements aimed at showing they’re ready for life post-graduation. Those requirements include SAT or ACT scores meeting or exceeding the college- and career-ready standard, getting a passing score on an AP or International Baccalaureate exam, scoring at least a Level III on the Armed Forces Qualifying Test, earning a career technical education credential, completing a N.H. Scholars program, or finishing a N.H. career pathway program of study.

Depending on how well students perform under those metrics, schools would be flagged for extra support if students aren’t reaching those benchmarks. Schools who need additional help would get it through Comprehensive Support and Improvement (CSI), and Targeted Improvement and Support (TSI).

Using the different metrics, schools would receive CSI help if they score in the bottom fifth percentile in the state or if their graduation rates are below 67 percent. TSI schools would be identified when subgroups consistently underperform according to the goals set by the state.

The state’s ESSA plan sets overall goals of 53.77 percent proficiency in math and 74.04 percent proficiency in English language arts by 2025. For different subgroups of students, the state has other goals. For example, students with disabilities are expected to hit 25.05 percent proficiency in math and 41.34 percent proficiency in English by 2025. Economically disadvantaged students are expected to be at 37.09 percent proficiency in math and 56.47 percent proficiency by 2025.

Some of those benchmarks could be hard to hit for school districts who are already strapped for cash and are seeing a decline in student enrollment. According to a report released last week from the New Hampshire Center for Public Policy Studies, it projects that state aid to school districts will shrink by $16 million over the next five years.

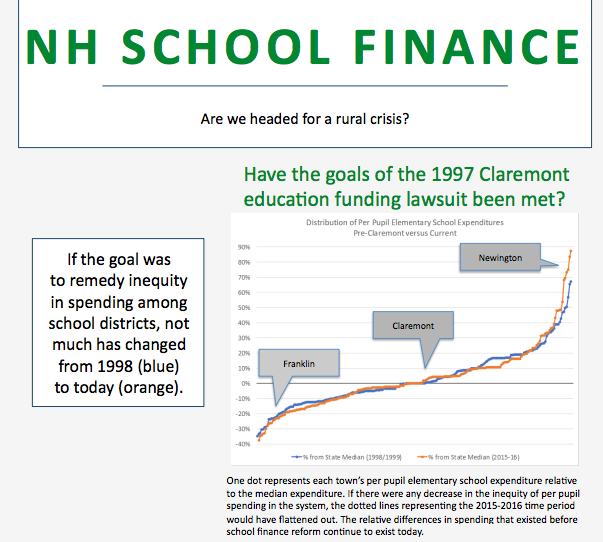

In December 1997, the N.H. Supreme Court issued its landmark Claremont decision, calling for equal access to an adequate education across the state, regardless of community wealth or property values. The policy institute concluded that little has changed since that decision was handed down.

The report notes that there has been a 40 percent increase in state aid to education since 1997, but there has also been a 15 percent decline in school enrollment statewide and significant disparities still exist from one community to another.

For example, property-poor communities like Claremont and Franklin continue to tax their residents at disproportionately higher rates to finance their education.

The research suggests that the disparities will continue and possibly worsen unless there comes a major change in how education is structured and funded.

In response, state education commissioner Frank Edelblut announced last week that the N.H. Department of Education would form its own committee, headed by the department Director of School Finance Caitlin Davis, to study the school finance problem and report its findings to a legislative panel that is considering changes to the state’s formula.

Since the release of New Hampshire’s ESSA draft plan, the education department has already received hundreds of comments, including some from civil rights advocates who want to ensure the state is held accountable for providing equitable learning opportunities, especially for marginalized students.

Now that the public comment period has ended, the state has about a month to tweak the plan based on the feedback before it’s submitted to the U.S. Department of Education for review and final approval in September.

Sign up for NH Journal’s must-read morning political newsletter.