Republicans in the state Senate are looking for a compromise with their House counterparts over the anti-critical race theory amendment contained in the proposed state budget.

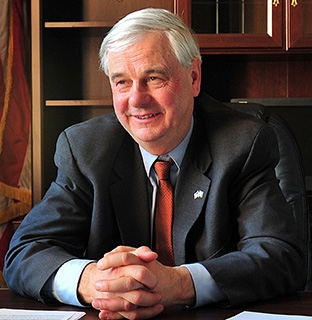

“I hope we’re able to find an acceptable version of the language that people can buy into and we can move forward with it,” said Sen. Jeb Bradley (R-Wolfeboro).

HB 2, the budget proposal approved by the House, includes language that bars the teaching of “divisive” topics on race and gender. The amendment, which replaces HB 544, is seen as critical if the Senate and Gov. Chris Sununu want the budget to pass.

Rep. Keith Ammon (R-New Boston), one of HB 544’s sponsors, said getting the critical race theory ban is a priority for the House GOP. He said it prioritizes storytelling over historical facts and has been creeping into the state’s education system for years.

“It’s slowly embedding itself in our institutions and it’s doing it with very little pushback,” Ammon said.

Last week, Rep. Ken Weyler (R-Kingston), House Finance Chair, warned the Senate that the ban on critical race theory is essential for the budget to pass. Weyler said the votes are simply not there if the Senate ditches the ban. Wyler himself considered critical race theory to be a “Marxist, anti-American, anti-White” program.

Bradley said people are worried about what is going on in school given the sometimes controversial idea presented under the critical race theory umbrella.

“People are pretty concerned about kids being taught in school, how this made them feel guilty for the way they are born,” Bradley said.

Bradley added people still need to be able to talk about racial inequities in society and in American history.

Critical race theory was developed in the 1970s and it prioritizes narrative and storytelling over data. In some materials it connects American racism with the signing of the Declaration of Independence. One of its best-known national advocates for critical re theory, Ibram X. Kendi, describes “whiteness” as inherently problematic to society and advocates discrimination as part of an “anti-racism” solution.

Ammon’s push to ban critical race theory has garnered plenty of opposition, including from Sununu who has expressed worries about the free speech implications of the ban. Last week, the New Hampshire Business and Industry Association, essentially the statewide chamber of commerce group, came out squarely against the ban, saying it will hurt the economy.

According to Jim Roche with the NH BIA, the proposed bans would halt discussions of race and gender inequality, among all state departments, educational institutions, and political subdivisions of the state, including cities and towns. The problem for Roche is that the ban would extend to private businesses that contract with the government. An estimated 1,000 businesses provide services to the state.

“Essentially, this language contains unnecessary restrictions on some private sector companies. We cannot support language where the state is in a position to dictate to private enterprises what they can and cannot discuss with their employees,” Roche said.

Ammon responded by questioning if the NH BIA is going “woke.” He says his real concern, though, is what sort of compromise the Senate will offer. Ammon is not interested in seeing the bill get watered down, noting conservatives have had enough of that kind of compromise.

“The visual is Charlie Brown and Lucy with the football, ‘Hey, we’ll give you this’ and then whoop, they take it away,” Ammon said.