This article originally appeared at JBartlett.org.

Americans’ confidence in large institutions, and government in particular, is collapsing. We no longer trust large, complex bureaucracies with little accountability to stick to their missions and do their jobs with honor and integrity.

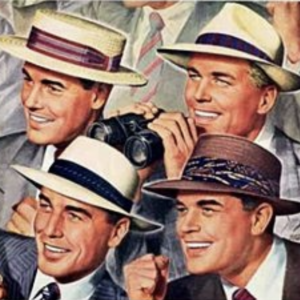

And yet many of our politicians continue to talk and act like business professors from 1956, arguing that we should concentrate power and authority in the hands of a few top-level managers.

“In the 1950s and 1960s, to be an able manager was to do four things well: plan, organize, direct, and control,” management professor Phil Rosenzweig wrote for Harvard Business Review back in 2010. “Leading business thinkers conceived of managers as rational actors who could solve complex problems through the power of clear analysis.”

Too many of our politicians take exactly this approach to governing. See a problem in society? Government will fix it! How? By crafting a plan, then organizing, directing and controlling citizens and/or businesses in pursuit of the plan’s objectives.

These politicians are stuck in the middle of the 20th century. They have absolute faith that the managers of a large, complex organization can see the future clearly, plan that future, and then build it through collective action organized by a handful of well-intentioned decision-makers.

This kind of thinking fell out of favor in business decades ago as managers, directors and shareholders realized that, among other flaws, this all-knowing manager approach was plagued by Hayek’s knowledge problem. A handful of elite managers can’t possibly have enough information to execute their vision successfully, even if it’s a great vision, which it often isn’t.

Government remains committed to this outdated approach even as its application at the hands of government managers has amassed a long and ignoble record of failure. That government is notoriously awful at managing things has not dampened the enthusiasm for giving government ever longer lists of things to manage.

That “small business” routinely tops Gallup’s poll of most trusted institutions, while Congress always sits at the bottom, is no mystery. Small businesses are directly accountable to consumers. Large bureaucracies are less so, and Congress hardly at all.

Yet we’re constantly pushed by those in power (especially members of Congress, the least trusted institution in America) to hand more control over our lives to large and distant bureaucracies.

Elites are constantly telling us that all of our problems can be fixed simply by giving them more power. It’s not remarkable that they keep saying this. It’s remarkable that so many Americans keep falling for it.

Professor Rosenzweig’s Harvard Business Review essay cited above was about Robert McNamara, the business management whiz kid elevated to Defense Secretary. He eventually managed the U.S. military’s involvement in Vietnam.

The concept of the all-controlling manager “shaped the developing profession, but many questions were left unanswered,” Rosenzweig wrote. “Planning and directing were essential, yes, but toward what ends? Organizing and controlling, of course, but in whose interest?”

McNamara thought he had the answers to those questions. Today’s activists for ever-larger government think so too.

Rosenzweig quotes historian Margaret MacMillan as a warning.

“McNamara spent much of his life trying to come to terms with what went wrong with the American war in Vietnam,” she wrote.

Rosenzweig expands on that assessment, writing that McNamara, successful in business but not in government, “sought to understand the sources of errors, hoping to square what he earnestly believed were good intentions with the massive waste and tragic loss.”

Note that “good intentions” were not enough to avoid “massive waste and tragic loss.” They never are. Often, the two go hand in hand.

People who think power solves problems believe they can avoid massive waste and tragic loss by hiring the best managers. But that’s not the answer. The answer is to reject the very idea that people and societies should be molded to the will of competent managers and large, unyielding bureaucracies.