All this week, NHJournal will be publishing stories about the impact of Watergate on American politics and culture, leading up to the 50th anniversary of the break-in on Friday, June 17.

There’s a school of thought that says history is made by great men and women. Presidents and dictators, generals and visionary inventors — those are the people who shape the course of human events.

Yet there are others whom history seeks out, everyday people who while going about their usual routine unintentionally and unknowingly blunder into great events. (Think Forrest Gump, only without the funny way of talking.)

Those people also reshape our times with their actions. But all too often, things turn out unhappily for them. This is the story of one such figure.

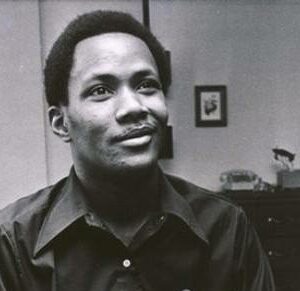

There was no reason to suspect anything unusual when Frank Wills arrived in the world in Savannah, Ga. in February 1948. Just another poor Black kid from the wrong side of the tracks whose story was sadly all-too-familiar: Parents separated when he was very young; dropped out before graduating high school; a future filled with uncertainty.

Frank bounced around for a while. He studied heavy machinery operations, got his GED, and worked on a Ford assembly line in Detroit. Chronic asthma forced him to quit the plant.

He drifted down to D.C., worked menial jobs at a few hotels, then landed the gig Fate had reserved just for him. Frank became a private security guard at the spiffy Watergate Office Building near the Potomac River. It was a hot location in the early 1970s; so choice, in fact, the Democratic National Committee had its headquarters on the entire sixth floor.

Which was where Frank Wills happened to be in the early morning of June 17, 1972. The 24-year-old security guard, who worked the midnight-to-7 a.m. shift for a whopping $80 a week, spotted duct tape stretched over a door lock. He ripped off the tape, but when he came back on his rounds, the tape had reappeared.

Frank rushed to the lobby and called Washington police, then led them on an office-by-office search. Five men were found inside the DNC headquarters. But they weren’t thieves. They weren’t there to take, but to leave something. Specifically, they were planting “bugs,” electronic listening devices to eavesdrop on private phone calls.

And something else was strange. The Washington Post reported police found “…almost $2,300 in cash (nearly $16,000 today), most of it in $100 bills with the serial numbers in sequence…”

White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler dismissed the incident as “a third-rate burglary.” But investigative journalists at the Post started digging, traced the break-in back to Nixon’s Committee to Re-elect the President (with its never-to-be-forgotten acronym CREEP), and things snowballed from there. The mounting scandal was shortened to the name of the place where it all started: Watergate.

It ultimately ended with Nixon’s resignation in August 1974.

Spotting that duct tape had set in motion a chain of events that concluded with a two-term president being driven from office. But what about the man whose vigilance had found it; what happened to him?

Frank Wills savored his 15 minutes of fame. But the celebrity treatment took its toll. One news account said he left the security position because he wasn’t given a raise after his historic discovery. A string of minimum wage jobs followed, but constant interview requests from reporters made him miss work.

He even had a cameo—playing himself—in the 1976 hit movie “All the President’s Men,” which led to making the rounds on the TV talk show circuit.

Then the attention vanished as quickly as it had arrived.

He eventually settled in North Augusta, S.C. so he could help his elderly mother after she suffered a stroke. The two barely made ends meet on her $450 monthly Social Security check.

There were two arrests for shoplifting, with the second sending him behind bars for a year. When his mother died in 1993, Frank donated her body to science because there was no money for a burial.

He scraped by as best he could: living quietly with cats, reading at the public library, and growing vegetables in order to eat.

Every so often there would be a media interview, usually connected to a significant anniversary of the break-in. Frank told the same story and answered the same questions he’d heard non-stop since the summer of ‘72.

“Everybody tells me I’m some kind of hero … I did what I was hired to do…” There was bitterness, too, as he continued, “…but still I feel a lot of folk don’t want to give me credit, that is, to move upward in my job.”

Frank made news one last time when he died of a brain tumor at age 52 in September 2000, alone and utterly forgotten—except for his “moment of history” inside a darkened office building exactly 50 years ago this month.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal