A New Hampshire state employee wants to become “The Man Who Would Be King.”

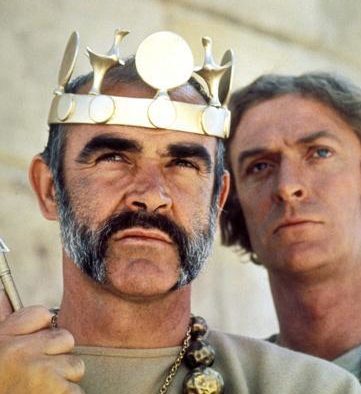

Like the characters in Rudyard Kipling’s 1888 short story of the same name – made in 1975 into what critics have called John Huston’s best film, one that its stars Sean Connery and Michael Caine recall as their favorite film experience – New Hampshire’s consumer advocate has wandered into a perilous desert. He has veered out of his lane as a supporter of residential electricity ratepayers to become an arbiter of regulatory convention.

Sean Connery and Michael Caine in “The Man Who Would Be King”

In a recent opinion column, Consumer Advocate Donald M. Kreis argues that the state’s Public Utilities Commission (PUC) should do whatever stakeholders agree upon when deciding a contested issue. He cites rulings about net metering (NM), a policy concerning excess customer-owned energy production sent to the grid, and ratepayer-funded energy efficiency as examples.

But what if stakeholders agree upon an action that may be wrong or unfair? Should the PUC, without question, agree to allow the implementation of policies that may not be in the best interest of the people who buy electricity? Should the PUC not be on the lookout for taxation through regulation, which harms ratepayers?

The PUC’s statutory responsibility requires it to ensure that utility rates and costs are just and reasonable, which entails non-discrimination. If a settlement agreement is unjust and/or discriminatory, the commission must reject it. The PUC can consider settlement agreements, but they are not required to adopt them. The commission may elect to ignore a settlement agreement if it determines that the agreement ignores the tenets of regulatory best practice, and the commission may have done so in its recent net metering docket.

To wit, the commission’s use of the word “all” in the docket order in reference to ratepayers indicates it believes the settlement agreement was unpersuasive about its claims of non-discrimination.

Net metering remains a classic example of this conundrum. State law requires utilities to take any excess energy produced by a renewable resource, such as a photovoltaic (PV) solar system, and compensate its owner according to a tariff in a PUC contested proceeding. If that tariff provides compensation for the use of utility poles and wires that transport power, that action shifts costs from the generating ratepayer to other ratepayers.

This cost shift occurs because a solar system seldom (if ever) matches its output with the power needed by its host. Instead, the system almost always uses a utility’s poles and wires to either get power from the grid or to put power back onto it. Giving some customers a credit for this use of utility property forces the utility to collect those costs from other customers.

Proponents of net metering say that this cost shift is small and therefore shouldn’t matter. But that raises a question of fairness and discrimination. Should any costs be shifted from one ratepayer to another? A small cost shift is still a cost shift. The record shows that this cost shift will triple in just two years.

The consumer advocate veers further into the desert when he writes that his main beef with the PUC concerns the agency’s attitude. He frets that the regulators pursue a policy agenda. But the agency has always pursued ideas that make sense to its members. The difference today seems to be that he does not favor those ideas and prefers the ideas of past iterations of the body.

Finally, the consumer advocate wants to rebuff legitimate questions about the efficacy of regulatory activity by insisting that the PUC return to acting like a court. His implication that it has stopped acting like a court is curious, considering the hundreds of adjudicative proceedings it has conducted in the past few years.

Our courts display the same weakness as any other human-operated institution. Courts frequently come to conclusions that contradict expectations. Higher courts often overturn rulings by lower courts. Knowledgeable people often disagree with court opinions. To imply that courts are somehow a pure bastion of reasoning and fairness flies in the face of reality, although they are better than the alternatives.

While the consumer advocate certainly has a right to express his feelings about the PUC, such claims may further widen the divide that exists today between conservative and progressive approaches to utility regulation.

As in “The Man Who Would Be King,” venturing into unknown deserts can bring delights, but it can also devolve into disaster. That’s the last thing we need for electricity regulation.