NH Commuter Rail Scheme Would Leave Property Taxpayers On the Hook

U.S. Rep. Chris Pappas hopes New Hampshire gets a new commuter rail service connecting Nashua and Manchester to Boston. Critics note how few Granite Staters use available rail now and don’t think local property taxpayers want to pick up the estimated $11 million tab to subsidize the trains.

Commuter rail is part of the $1.2 trillion infrastructure spending package pushed by President Joe Biden and supported by all the members of New Hampshire’s congressional delegation. Biden signed the bipartisan infrastructure bill, which includes $66 billion for rail, in November.

“This is a project that continues to bubble from the bottom up here in New Hampshire,” Pappas told Manchester’s InkLink last summer about the Capitol Corridor rail project. “I hear about it everywhere I go, residents who are looking for an opportunity to get to work, businesses that are looking to attract the kind of talent they need, and from local leaders who understand this can be an economic engine for New Hampshire.”

The train service would potentially go from Manchester through to Lowell, Massachusetts, with stops in Nashua and at the Manchester-Boston Regional Airport.

Greg Moore, with the libertarian American for Prosperity organization, said New Hampshire cannot afford the fare. The service cannot operate without a taxpayer-funded handout, he said.

“Every state study has shown that it would require substantial taxpayer subsidies to benefit a small number of riders,” Moore said.

Moore said there are better ways to solve commuting problems that meet 21st century needs. He suggested private services like Turo or ZipCar, as well as Uber and Lyft.

“Trying to jam an expensive 19th-century transportation solution onto the hard-working taxpayers of New Hampshire makes no sense,” he said.

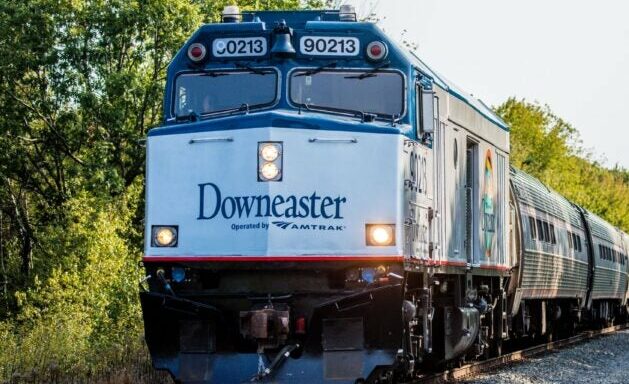

A common argument from opponents of expanded rail is Granite Staters rarely use the service that’s currently available. The Amtrak Downeaster, for example, connects the Seacoast towns of Dover, Durham, and Exeter with Maine and Boston. According to Amtrak, New Hampshire riders make up less than 20 percent of the total ridership.

In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, fewer than 2,000 trips a week began or ended in the Granite State. During the pandemic when ridership fell, the number of trips originating or ending in New Hampshire fell to 362 per week. Neither of those numbers is enough to sustain rail service without taxpayer subsidies.

In fact, Amtrak — often hailed as a success story — has received annual federal subsidies of $1.5 billion to $2 billion, in addition to the new billions from the bipartisan infrastructure bill. And the only reason service in the Northeast “pays for itself,” as advocates claim, is because of inventive bookkeeping that hides a huge backlog of needed maintenance and the subsidies it receives from state governments.

State Rep. George Sykes, D-Lebanon, a member of the House Transportation Committee, said every form of transportation, from air travel to bus service, is subsidized by taxpayers to some extent.

“There’s no free lunch when it comes to transportation,” Sykes said.

Sykes said rail service would be a net financial positive for the state in the long run when factors like increased development and savings on highway maintenance costs are considered. Paying for the service through taxes or fees just goes the territory, he said.

“My question to (those opposed to rail) would be, name me one aspect of transportation where they don’t have to pay for, one way or another.”

Sykes’ colleague on the Transportation Committee, Aidan Ankarberg, R-Rochester, doesn’t want his voters to have to pay for a service they are not going to be able to use. He recently filed a bill that would keep any state funding from being used for the rail project.

“It is not fiscally responsible or the New Hampshire way to expect my constituents in Rochester to pay for a commuter rail in Manchester that very few people will use,” he said. “My bill protects Rochester and other Granite State taxpayers from this boondoggle before it begins.”

Ankarberg said the most recent Department of Transportation report on the commuter rail, which estimates the state would need to subsidize the service at $11 million, is several years old and out of date. The true cost for the service to taxpayers is likely closer to $16 million, he said. That money would come from increased property taxes, or cuts to education funding, he said.

“While current estimates aren’t available, the DOT previously suggested raising statewide property taxes by $15.7 million or diverting 5 percent of our education funding in order to cover the commuter rail’s operating and management costs,” he said.

That kind of spending isn’t going to catch on in New Hampshire, according to Moore.

“Thankfully, there is little appetite in the state legislature for saddling state taxpayers with this backward approach,” Moore said. “New passenger rail isn’t happening anytime soon.”