Remote Learning Left Many NH Students Behind, New Assessment Shows

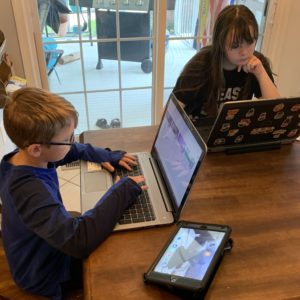

As COVID concerns closed down classrooms and sent students to Zoom screens last year, New Hampshire students lost ground across the board, according to assessment test data released this week. The numbers show Granite State student performance plunging in math, and falling in reading and science, after more than a year of COVID-19 schooling.

“It is clear and understandable that trauma from the pandemic continues to impact schools, students, and teachers,” said Department of Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut.

New Hampshire’s numbers align with national trends showing school children are suffering a learning gap due to COVID, school shutdowns, and remote learning programs. Minority students and students from low-income families have suffered the worst losses, national data show.

Scott Marion, executive director of the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment, a Dover-based technical consulting firm, said some of the New Hampshire losses are minimal but still noticeable. The losses are almost entirely due to remote learning, he said.

“In general, we know that the students who learned remotely fared worse than those who learned in-person. While everyone’s scores suffered nationwide, the test scores for those students who had in-person learning suffered less. This was generally the case in New Hampshire as well, especially in mathematics,” Marion said.

Statewide, 52 percent of students scored proficient or above proficient in reading for 2021, compared to 56 percent in 2019. Science scores averaged 37 percent proficient/above proficient in 2021 compared to 39 percent in 2019.

The real damage was done on math scores, which fell from 48 percent at or above proficient to 38 percent two years later — a dramatic drop of 21 percent.

Proficiency for English Language Arts (ELA) at the third-grade level was 44 percent in 2021, compared to 56 percent in 2016, 54 percent in 2017, 55 percent in 2018, and 52 percent in 2019. Proficiency for math at the third-grade level was 45 percent in 2021, compared to 57 percent in 2016, 55 percent in both 2017 and 2018, and 57 percent in 2019.

Eighth-grade proficiency for ELA was 49 percent in 2021, compared to 62 percent in 2016, 58 percent in both 2017 and 2018, and 53 percent in 2019. Proficiency for math at the eighth-grade level was 33 percent in 2021, compared to 47 percent in 2016, 46 percent in 2017, 47 percent in 2018, and 45 percent in 2019.

There are also fewer tests being completed. In 2019, the year before COVID forced schools to shut for months at a time, there were 91,050 student assessments for Math. In the spring of 2021, 73,406 were done.

In reading, there were 90,785 assessments done in 2019 compared to 72,880 in 2021. Science participation saw 37,720 assessments complete in 2019, and 28,495 in 2021.

The Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy, based on Concord, has also reported on the connection between less class time and lower test scores.

“School districts that offered less in-person instruction last year saw fewer students pass end-of-year standardized tests, a new academic study of student performance in 12 states has found,’ the Bartlett Center reported, citing the work of researchers from Brown University, M.I.T., and the University of Nebraska at Lincoln.

According to a report from the consulting firm McKinsey, the learning gap experienced by school students now, especially minority students, could hold those students back economically in the years to come.

“Our analysis shows that the impact of the pandemic on K–12 student learning was significant, leaving students on average five months behind in mathematics and four months behind in reading by the end of the school year,” the report states.

The pandemic made the education gaps that already exist for minority students and students from low-income families even worse than before.

“In math, students in majority Black schools ended the year with six months of unfinished learning, students in low-income schools with seven. High schoolers have become more likely to drop out of school, and high school seniors, especially those from low-income families, are less likely to go on to postsecondary education,” the report states. “The fallout from the pandemic threatens to depress this generation’s prospects and constrict their opportunities far into adulthood.”

The pandemic saw schools shut down in March 2020. Most public schools reopened in New Hampshire in the fall of 2020, but went to remote learning for long stretches over the winter months. As cases of COVID spike this winter, a few schools are entering into some form of remote learning,

Critics of the “closed-classroom” response to COVID-19 have repeatedly noted the virus has posed very little risk to school-age children. There hasn’t been a single COVID death of a Granite Stater under the age of 20, and fewer than 50 people in that age group have been hospitalized during the entire pandemic.

Gov. Chris Sununu has said he doesn’t see a return to a state-wide remote learning program. “Kids really need to be in school, they want to be in school and that’s the best place for their education,” Sununu recently told NH Journal.

New Hampshire teachers are doing a tremendous job during the pandemic, Edelblut said, and the DOE will work hard to make sure students and families will be able to catch up.

“New Hampshire will continue to address learning loss through customized, unique, and engaging learning platforms that focus on individual student achievement and success,” he said. “Parents continue to have valid concerns about their children’s academic progress. Measurable improvement is a goal that we can all stay focused on and work toward.”