What Factors Led New Hampshire to Be Ground Zero for the Opioid Crisis?

It’s a well-known figure that New Hampshire has the second-highest per capita drug overdose deaths in the United States, right behind West Virginia. The state also has the highest rate of fentanyl-related overdose deaths per capita, leading researchers, health care providers, first responders, and lawmakers to wonder what about the Granite State makes it one of the most ravaged by the drug epidemic.

That was the subject of a forum at Dartmouth College last month, which included Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the National Institutes of Health; Lisa Marsch, director of the Dartmouth Center for Technology and Behavioral Health (CTBH); and U.S. Rep. Annie Kuster, D-N.H.

“Not only did we want to bring together a broad group of stakeholders about the crisis in our communities, but we also wanted to have a discussion about the response to the crisis,” Marsch told NH Journal. “Why New Hampshire? What’s going on in New Hampshire that’s distinct and giving rise to it?”

To find out why the rate of opioid overdoses increased by nearly 1,600 percent from 2010 to 2015, the New Hampshire Fentanyl “HotSpot” Study was funded by the NIDA. The rapid epidemiological study focuses on the increase of overdoses from fentanyl, a drug that is 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin and often is mixed with heroin. In Phase I of the study, researchers spoke with medical responders, law enforcement officers, state authorities, and policymakers.

The study was conducted by the CTBH, in collaboration with the National Drug Early Warning System, and funded by the NIDA.

Marsch said they quickly realized that they needed to speak with opioid users to better understand the trajectory of fentanyl use, the tracking of the drug, and fentanyl-seeking behavior in order to effectively inform policy and community response.

Phase II was then commissioned to do just that. March’s team interviewed 76 opioid users, 18 first responders, and 18 emergency department clinical staff from six counties in New Hampshire during October 2016 to March 2017. The results of the study are not publicly available yet, but Marsch presented key findings at the forum.

The report found that the recent increase in the availability of fentanyl is because it is less expensive and quicker to take effect than heroin. However, the high doesn’t last as long and requires users to use more often, increasing the risk of overdose.

About 90 percent of the drug users interviewed for the study indicated they actively sought out drugs that would cause overdoses.

“We want whatever is strongest and the cheapest. It’s sick,” one respondent said. “I now me using, when I hear of an overdose, I want it because I don’t want to buy bad stuff. I want the good stuff that’s going to almost kill me.”

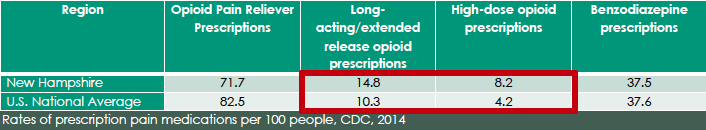

Marsch said the study allowed researchers to analyze “a whole array of factors that set up the perfect storm” for New Hampshire to be one of the hardest hit states by the opioid crisis. She said the Granite State consistently rates in the top 10 states with the highest drug use rates and opioid prescribing by doctors exceeds national averages.

New Hampshire is also in close proximity to a supply chain for the fentanyl drug in Massachusetts.

According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s 2014 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary, most heroin supplies in the New England region are brought in from New York along the vast interstate highway system, naming I-95 and I-93 as the major routes for New Hampshire’s heroin traffickin. The report also named Lawrence, Mass. as a main distribution center for northern New England states.

The New Hampshire “HotSpot” Study pointed to these other factors contributing to the heroin and fentanyl crisis in the Granite State:

- Treatment admission rates per capita are lower than both the national average and all other New England states

- N.H. has the lowest per capita spending on treatment in all of New England and it’s the 2nd lowest in the nation

- The state has the lowest rate of Suboxone, a medication used to treat opioid addiction, providers per capita in all of New England

- Public health funding per resident is lower than the national average and surrounding states

- N.H. is the only state in the Northeast with no needle exchange program (The legislature recently passed a bill legalizing the programs and Gov. Chris Sununu said he would sign it.)

- The state’s rural setting keeps people in tightly knit social networks and has limited access of “things to do.”

“The economic factors, the rural nature, the politics, lack of resources, and the close proximity to the source of these drugs has created a really bad scenario for the state,” Marsch said.

In order to curb the alarming trend of opioid overdose deaths in the Granite State, the researchers suggested the state increase public health resources for substance use prevention and treatment, expand prevention programs in elementary and middle schools, assist physicians with understanding opioid prescribing, and collaborate with Massachusetts on addressing the manufacturing and trafficking of fentanyl and other opioids.

At the forum, Kuster, who co-chairs the House Bipartisan Task Force to Combat the Heroin Epidemic, said she was confident that Granite Staters’ “certain blend of tenacity and creativity” will help find solutions to this epidemic. Officials point to the Safe Station program, which allows anyone who is struggling with drug addiction to go to fire stations in the state to connect with recovery resources, as a New Hampshire solution to the drug epidemic.

Yet, Kuster was worried that it would be difficult to get more funding and resources under President Donald Trump’s leadership.

“We cannot get this job done without Medicaid expansion. I’m concerned about cuts for mental health and behavioral health services,” she said. “If they’re [Republicans] going to walk the walk, as they have talked about opioid addiction, they’ve got to fund the programs that will bring the services to our communities.”

Sign up for NH Journal’s must-read morning political newsletter.