Board of Ed Talks Lionheart Academy Behind Closed Doors

Facing accusations of mismanagement and a potential conflict of interest, representatives for the Lionheart Classical Academy met with the state Board of Education behind closed doors on Monday.

Lionheart’s board of trustees representatives asked Board Chair Drew Cline for the non-public meeting to protect the reputations of the people discussed. The minutes for the hour-plus non-public meeting were immediately sealed, but it is likely the topic of discussion was the two letters sent to the BOE laying out concerns about the future of the charter school located in Peterborough.

Founder and major donor Fred Ward alerted the BOE last week about an alleged conflict of interest connected to the Sharon Road building the school leases for more than $24,000 a month.

According to Ward’s letter, written by attorney Richard Lehmann, former Lionheart Trustee Barry Tanner failed to disclose his business relationship with landlord Ophir Sternberg when he negotiated the lease and the naming rights.

Lionheart Academy takes its name from Sternberg’s Lionheart Capital. The $1 million donation Sternberg agreed to make in exchange for the naming rights has largely evaporated, according to Ward.

Lionheart parent Kevin Brace sent a letter to the BOE Monday morning with his worries, including the fact the trustees seem to have lost their conflict of interest statements.

“At the Sept. 12, 2024 LCA Board of Trustees Meeting, the board announced that it had lost the Conflict of Interest forms that the board signed at the May 2024 Board of Trustees meeting. It should be noted that Barry Tanner was the Chairman at the time of that meeting, and his disclosure is now missing. It should be noted that I requested these forms under Right to Know and the board never notified me that the documents were missing. In light of the allegations in Dr. Fred Ward’s correspondence to The New Hampshire State Board of Education, the fact that these documents are now missing is extremely alarming,” Brace wrote.

It is standard practice for boards to have members sign a statement acknowledging they understand the conflict of interest policy, or law, that applies to their institution.

Contacted by NHJournal, Tanner declined to discuss his business with Sternberg. According to Ward, Tanner and Sternberg sought to buy the historic Hancock Inn together around the 2021 time frame when the lease and naming deals were negotiated.

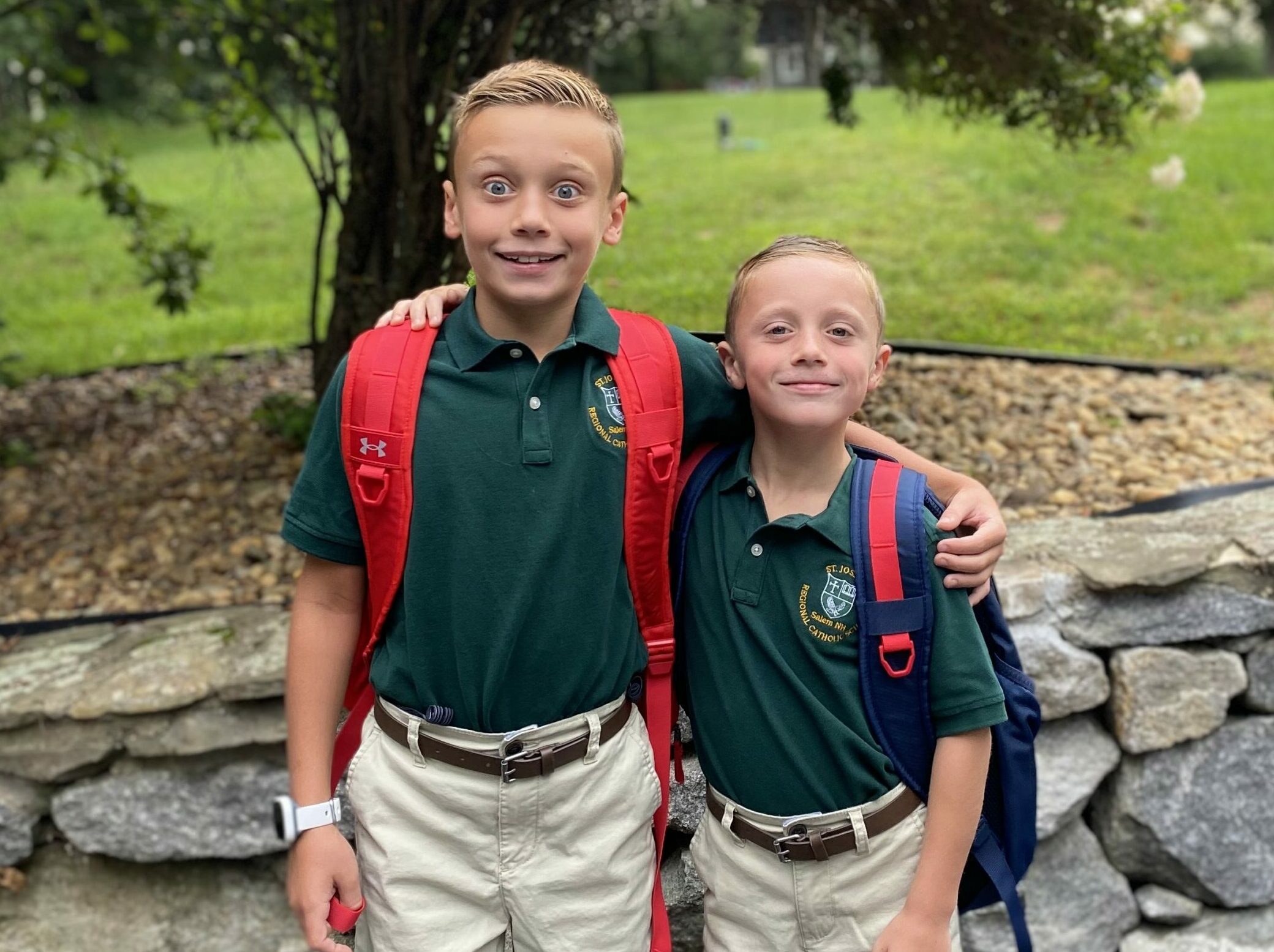

Brace, a former corrections officer with a background as a civilian police commissioner, started going to board meetings this summer after Executive Director Kerry Bedard was fired. He said he was shocked to find out what had been happening.

“As the parent of a child attending Lionheart, I could not sit back and watch an out-of-control board who allowed a landlord to overcharge for rent, accepted junk stock, and refuse to follow state law,” Brace told NHJournal.

Brace’s letter to the BOE raises several questions about the management of the board, including the concern the board is meeting illegally outside of posted meetings. Charter schools are legally public, and the boards are required to follow the same open meeting and public records laws as public school boards.

“On July 26th 2024, LCA Board of Trustees Chairwoman [Kimberly Lavallee] admitted to Commissioner [Frank] Edelblut, [Right to Know] Ombudsman Thomas Kehr, and I in an email that the LCA Board of Trustees had a meeting and took action that was never noticed to the public,” Brace wrote.

Brace also claims board members use a messaging app to conduct board business.

“I was notified by a parent that some LCA Board members were on an app called ‘Band,’ and that they were acting in their official capacity as board members. I requested a copy of those conversations, and the board did not turn them over to me,” Brace wrote.

One of the major concerns Ward raised in his letter, Lionheart’s financial stability, seems to be addressed thanks to a generous, anonymous donor. Hours after Ward sent his letter to the BOE last week, Lionheart announced it was getting a $5 million endowment from an unnamed individual.

But Brace is worried the current board is not up to the task of managing a gift of that size.

“Given the LCA Board of Trustees track record of handling large donations, I believe the State Board of Education should examine this donation,” Brace wrote.

Sternberg agreed to give Lionheart $1 million in cash through regular $100,000 installments in exchange for the naming rights, according to Ward. However, after one payment was made, Sternberg’s donation was changed to a gift of stock in his investment company, according to Ward’s letter. The school was locked out from accessing that stock for about a year. By the time it was available to cash out, Lionheart’s stock was worthless, Ward states.

Both Ward and Brace are worried the school is stuck with a lease agreement that requires them to pay for upgrades to the building without a written stipulation they can buy the property at any point. Braces blames poor board oversight for this predicament.

“They were supposed to be working for the school, not the landlord,” Brace said.

It’s not clear yet if the BOE will take any action on the Ward and Brace letters. Brace told NHJournal he simply wants to make sure the school can continue educating students like his daughter.

“All I am asking for is for the State BOE to provide some much-needed oversight. I do not want the school to fail. It’s hard for me as a parent to trust that this current board is really doing the right thing, especially given their recent history of turning a blind eye and telling everyone that things are great,” Brace said.