For an alternate viewpoint, see “Counterpoint: Rethinking the Significance of Presidential Debates.”

What nominee would bet on the proposition that the presidential debates don’t matter and then choose not to prepare?

Jimmy Carter’s desultory prep in 1980, combined with Ronald Reagan’s reassuring and masterful performance — “There you go again” — arguably turned a close election into a landslide that reshaped American politics for a generation. Barack Obama‘s uncharacteristic lack of discipline in the lead-up to his first encounter with Mitt Romney in 2012 led to an excruciating 90 minutes that drove Democrats into mass hysteria. He won the election anyway, although only after a hypersonic Joe Biden dominated Paul Ryan in their vice-presidential exchange, and then Romney himself was shredded on the issue of Benghazi in the second debate — by a tag team of Obama and the debate moderator.

So do debates matter? Like most things in life and politics, sometimes yes, and sometimes no. Here are some other examples.

1960: Vice President Richard Nixon was running on the slogan “Experience Counts” when he made the mistake of debating John F. Kennedy. JFK used his opening statement — eight minutes long, without a single note — to define the terms of this high-stakes clash, which Nixon then largely accepted as he quibbled like a point-by-point high school debater with Kennedy’s arguments while often repeating them literally word for word.

Without the debates, especially the first one, it’s hard to imagine that the youngest president elected in one of the closest contests in history would have reached the White House. (And Kennedy’s triumph wasn’t all about image. The oft-told story that voters who listened on the radio instead of watching on television believed Nixon prevailed ignores the reality that those voters couldn’t watch: They were concentrated in pre-cable rural areas and the mountain west, which already heavily favored Nixon.)

1976: After an unexpectedly strong performance in the first debate, with the once beleaguered Gerald Ford having closed a yawning gap with Jimmy Carter to just 2 percent, Ford’s momentum stalled for a crucial period after he insisted in their second confrontation that “there is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe.”

There is a convincing case that rhetorically freeing Poland did make the decisive difference in an election where a switch of a few thousand votes in a few states would have yielded an Electoral College majority for Ford.

1992 … when an indelible image truly did matter. The most memorable moment of the debates that year was incumbent George H.W. Bush glancing impatiently at his watch as an earnest questioner in the town hall audience asked him how the recession had affected him personally. The episode was a powerful metaphor for a presidency that appeared tired and out of ideas in a country yearning for change. Did it determine the results? Not by itself, but it does suggest a guideline: Maybe candidates should take their watch off before mounting the debate stage.

In other cases, assessing the effect of these face-to-face encounters is hard. How much did Donald Trump’s crass antics hurt him in 2016 and 2020 — and less noticed, how much did his emphasis on trade and immigration in the early innings of his first clash with Hillary Clinton help him in the Blue Wall states that crumbled on Election Day?

And sometimes, as in 1988, 1996 and 2008, debates won’t bend the campaign arc at all unless the likely winner’s performance is the unlikely political equivalent of bellyflopping into an empty swimming pool.

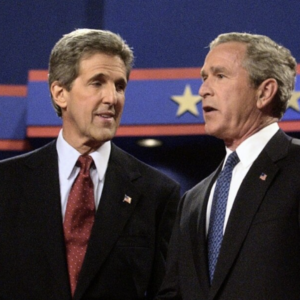

Finally, for me, there’s also a painful irony here: You can win all of the now customary three presidential debates and still lose the election — which, as the Gallup Poll showed, is precisely what happened with John Kerry’s narrow defeat in 2004.