Many of us grew up watching World War II newsreels of heroic Americans vanquishing evil villains and liberating the oppressed. Powerful imagery abounded of ecstatic citizens of Paris or Rome showering our GIs with flowers, hugs, kisses, and more. And it wasn’t just the great cities. Countless European towns, villages, and hamlets welcomed their U.S. liberators with joy incomprehensible to those who have never been subjugated by brutal, evil tyranny.

And then there were the concentration camps, where survivors clinging to life suddenly realized they were not going to die horrible deaths. They saw these motivated young American GIs as no less than liberating angels dispatched by God.

As a lover of history, I watched these scenes of joyous liberation and lamented that I would never get to experience the wonders the Greatest Generation enjoyed as they helped good triumph over unspeakable evil.

Then — unexpectedly — in 1991, I did get a taste of a tumultuous hero’s welcome from a grateful population that we Americans rescued from hell.

I was one of a half-million service members sent to the Persian Gulf for Operation Desert Storm to liberate Kuwait from the evil clutches of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. After a devastating Allied air campaign, American ground forces moved from Saudi Arabia through multiple minefields and into burning Kuwaiti oil fields to engage an enormous Iraqi army that had been preparing for months. My USMC infantry battalion was part of an unstoppable 1st Marine Division assault. Four days later, the Iraqis sought a ceasefire.

By that time, we were dug in on the outskirts of the great airport near Kuwait City. The rapid denouement was welcomed by us all, as we had been wearing the same uniforms for weeks and were braced to battle it out for months if necessary.

Before long, we loaded onto trucks and transport vehicles to head back to Saudi Arabia. Our return route took us not through burning oil fields, but through a shot-up and devastated Kuwait City. There was no electricity, but there were plenty of shell holes — along with occasional dead bodies.

As we slowly rolled south, we eventually saw a few native Kuwaitis. And then more. And then still more.

Soon, the streets were lined with Kuwaitis. Those Arabs welcomed the Americans with boundless joy. As with Paris in 1944, there were tears, hugs, flowers, and joy. (But no wine!)

We realized we had given these people new lives — that they were free from the prospect of spending the rest of their existence being murdered and oppressed by Hussein’s secret police. We shared in their joy. One had to be there to fully appreciate the affection that flowed toward us.

It was beautiful beyond words.

And as Americans, we loved being loved.

America has long been that heroic entity to so many, going back to World War I, when a million doughboys went “over there” to France in 1918 to give an utterly exhausted Allied effort what was needed to end the war, intended to end all wars. How the weary French must have loved seeing so many fired-up Yanks willing to give their lives for their cause.

We reprised that role during the Cold War, when, after spending countless billions of dollars and deploying many millions of GIs around the world, we finally vanquished Soviet communism so the many ancient states of Eastern Europe could again breathe free.

We offered up tens of thousands of American lives to keep South Korea sovereign and eventually free in the 1950s, as opposed to becoming part of the horrific nightmare that North Korea was — and is.

Countless Americans are still missing in Asia, while the remains of tens of thousands can be found in cemeteries all over Western Europe.

So why are we not as beloved today as we once were?

An honest review of our history will find chapters less heroic than rescuing Rome, preserving Paris, or saving Seoul.

In 1953, the CIA sponsored coups in Iran and Guatemala that had tragic, unforeseen, and lasting consequences. The CIA’s 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion fiasco helped solidify a communist Cuba that endures to this day. We are still recovering from the misbegotten American involvement in the Vietnam War from 1959 to 1975. Invading Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003, respectively, resulted in many years of conflict with mournful results. By fomenting Chilean or Central American regime changes, we created suspicion and mistrust of an America that was previously admired — if not beloved — around the world in 1945.

Which brings us to 2026 and Venezuela. And yes, oil is part of the equation, as it was in Kuwait in 1991.

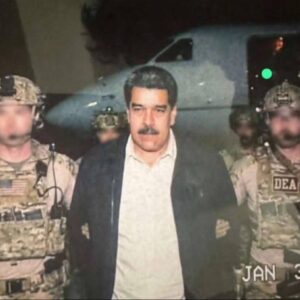

News that President Donald Trump apprehended and incarcerated Venezuelan strongman Nicolas Maduro was unsettling, exciting, or horrifying, depending on whom one talked to. What next?

There are many variables and many possible scenarios, which we needn’t go into here. Time will tell. But what should happen in the short term is prudent pondering by both Trump supporters and Trump adversaries.

Trump supporters, in particular, should not be afraid of asking uncomfortable questions — the type of questions that should have been asked more vigorously by more people in the 1960s, when we were sucked into a Vietnam quagmire from which we could not escape.

And Trump adversaries, especially those suffering from terminal Trump Derangement Syndrome, should also pause and ponder. Too many have already instinctively condemned the entire Venezuelan adventure, when there is still so much left to unfold and understand. This, unfortunately, commits them to hoping for a bad outcome for the Trump administration — and thus for America.

So let’s all wait and watch for a bit. It will soon be apparent whether Maduro is more Castro or Noriega — or vice versa.

And let’s also ponder what Americans once did to be beloved as the heroic liberators of Paris, Rome, or Kuwait City, rather than the sordid schemers of Tehran, Guatemala City, or Havana.