In January, news broke that Shannon Buttermore—a Gilford mother of three—had been denied a kidney transplant by Dartmouth Hitchcock because she refused a COVID vaccine shot. Dartmouth’s actions were an open violation of New Hampshire’s 2022 “Patients Bill of Rights,” which prohibits the denial of medical care on the basis of vaccination status.

Although Buttermore had been losing kidney function since October, months passed without anyone in government doing anything to stop Dartmouth’s illegal conduct. “I don’t understand how a hospital can just ignore state law,” Buttermore said.

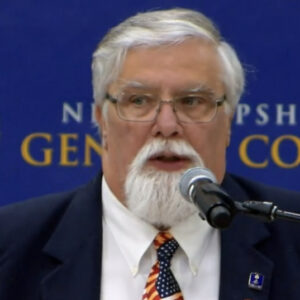

But with press coverage mounting in January, the case caught the attention of House Speaker Sherman Packard. In an unusual move for someone who is not a law enforcement officer, regulator, or prosecutor, Packard sent Dartmouth an open letter telling them to obey the law.

Although the House Speaker had no law enforcement powers, Packard’s letter helped bring the case additional media attention. A few days later, following engagement by the New Hampshire DOJ—an agency that is not exactly full of conservatives—Dartmouth publicly agreed to allow Buttermore, and others who have not received the COVID vaccination, to apply for a transplant.

Yet Dartmouth’s policies continue to deny life-saving organ transplants to patients who refuse any standard vaccine other than the COVID shot. In other words, Dartmouth plans to continue violating New Hampshire law as long as it can get away with it.

Buttermore’s case is just one illustration of a longstanding problem facing Republican-passed laws in New Hampshire. When Republicans enact laws on any polarizing issue, the personnel in our state agencies often choose not to enforce them. Although solving this problem will eventually require systemic changes, there are many short-term workarounds that Republicans can use to mitigate the personnel problem tomorrow.

New Hampshire Republicans sometimes pass bills that lack any enforcement mechanism—such as New Hampshire’s Second Amendment Sanctuary law—and therefore cannot compel anyone to do anything. But that is not what happened with the Patients’ Bill of Rights.

Because it was placed in Chapter 151, which regulates health facility licensing, the Patients’ Rights law has genuine legal penalties. Under RSA 151:16, a first violation by a healthcare provider is a “violation,” equivalent to a minor traffic offense. Under 151:16-b, the Department of Health and Human Services can also hit violators with a $2,000 administrative fine.

This only underscores Buttermore’s question. If the law is enforceable, why did it fall to the House Speaker—a legislator—to act as a de facto sheriff? And how can Dartmouth’s organ transplant policies continue to openly defy democratically-enacted laws?

The problem is that, even when our laws do contain real enforcement mechanisms—as in the Patients’ Bill of Rights—any law enforcement mechanism needs human law enforcers to operate. If the enforcers we hire are all progressives—or just weak-willed Republicans—then even well-crafted laws will gather dust on the roadside.

Politicians can take certain limited measures to encourage people to obey the law. In this case, Speaker Packard successfully acted as a kind of informal police officer by garnering media attention. The Executive Council, led by Councilor Dave Wheeler, has also indicated it will not approve contracts with Dartmouth Hitchcock until it agrees to obey the law. Yet indirect political leverage is no substitute for actual law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and agencies dedicated to faithfully enforcing our laws.

The hard truth is that we have a personnel problem. Conservatives simply do not occupy many New Hampshire prosecutors’ offices or, evidently, any positions of power at all in the state Department of Health and Human Services. If nothing changes, Dartmouth may, with impunity, simply choose to continue illegally denying healthcare to any patient less courageous than Buttermore.

An identical problem has long faced New Hampshire’s better-known “CRT ban.” In 2021, New Hampshire passed its Prohibition on Teaching Discrimination, which prohibits public school teachers from teaching that any group is inherently racist or privileged—or that some races should be discriminated against. Unfortunately, even before the law was enjoined last year by New Hampshire’s federal district court, employees in New Hampshire’s Department of Education had effectively nullified it.

The law’s main enforcement mechanism was meant to be the Educator Code of Conduct. Under the law, any prohibited teaching is a violation of the state’s Educator Code—which the DOE alone can enforce. This made sense: the DOE has a ready-made system in place to investigate teachers, including its own on-staff investigator. The Educator Code says “the department shall undertake an investigation” if it has reason to suspect that a violation has occurred.

After the law was enacted, New Hampshire parents filed credible reports with the DOE that more than 67 New Hampshire educators, in 27 SAUs around the state, were teaching that groups of people are inherently racist and/or privileged. In some cases, teaching that violated the law—such as teaching that white students are privileged—was even posted on district websites.

But staff at the DOE categorically refused to investigate any of these alleged violations, no matter the strength of the evidence. Instead, they said that parents should report teachers under the Educator Code to the state’s Commission for Human Rights—a concept that makes no legal sense.

This nullification of our “CRT ban” is important because the law was not just well-intentioned, but well-crafted—containing multiple, creative enforcement mechanisms distributed between different agencies. Yet even an expertly-crafted law is no substitute for dedicated conservative personnel committed to enforcing the law. If our state agencies all support CRT, or are at best willing to turn a blind eye to lawbreaking, then dozens of teachers can still openly violate the law and treat it as a joke.

In short, policymaking does not consist of law alone. Even if Republicans rewrite every New Hampshire statute, their lawmaking will amount to whistling into the void without government personnel who want to implement it. Our state agencies and the parties they regulate—such as hospitals and schools—have formed an unspoken consensus that conservative-coded laws are pretend statutes passed by a mock legislature. Only nonpartisan or progressive-coded statutes have the aura of real law and bear the solemn mantle of democracy.

Fixing our personnel problem will require big-picture cultural solutions. For example, New Hampshire conservatives can no longer write off all unelected public service as an inherently leftist occupation. They must also outgrow the “Nirvana fallacy,” in which conservatives dismiss attainable goals like hiring conservative superintendents and focus exclusively on remote, utopian goals like replacing the entire public school system with anarcho-capitalism.

Yet changing the way conservatives think about politics is an ambitious project that will take time and resources. In the meantime, there are several practicable, short-term solutions—things Republicans can implement this term—that would greatly mitigate the personnel problem.

First, when Republicans are drafting bills on any contentious issue, they should offset the risk of non-enforcement by including more draconian penalties than would otherwise be reasonable. For example, Republicans should amend the Patients’ Bill of Rights so that any intentional violation is a misdemeanor crime. Intentional violations by healthcare providers should also carry much higher minimum financial penalties—as well as higher maximums than the current $2,000.

Most importantly, a law like the Patients’ Bill of Rights should have a lengthy statute of limitations for prosecution. This would mean that, even if there are no conservative regulators in New Hampshire, Dartmouth must consider that state agencies could have right-wing personnel five years into the future. In effect, passing a lengthy statute of limitations is like summoning ghosts from the future to enforce your policy.

While this solution sounds simple enough, this would itself require a significant cultural change for Republicans. Traditionally, Republicans are much more timid about drafting strong enforcement mechanisms than Democrats. For example, in Democratic sanctuary states like Vermont, the law requires that any police officer who collaborates with ICE must be disciplined or fired. In contrast, when New Hampshire passed its “Second Amendment sanctuary state” bill, it included no mandate that police officers follow the law.

The reality is that, because Republicans have a much harder time recruiting faithful government personnel, conservatives actually need to be even tougher than the left in crafting statutory enforcement mechanisms. Without conservative personnel to enforce their laws, conservatives need enforcement clauses that cast longer shadows.

Secondly, legislators can create modest civil remedies against agencies that nullify democratically-enacted laws. For example, an amendment to the “CRT ban” might say that, if the Department of Education categorically refuses to investigate violations of a particular provision of the Educator Code, any affected student may obtain legal relief against the Department in court. This enforcement mechanism could yield tremendous returns by motivating the enforcers themselves to spring into action across the state.

Third, conservatives can divide factions of the left’s coalition against each other by passing bills in which sections of the left have competing interests. For example, Sen. Keith Murphy’s original version of the Students First Act would have required that, if any school district chooses to increase spending, it must increase teacher pay before it can hire new administrators such as diversity professionals. Although not many public school teachers are conservative, Murphy’s original bill would have put even left-leaning teachers at odds with the teachers’ union and progressive administrators. One faction of the left’s traditional coalition would have been incentivized to invoke the new law against another.

Finally, and on a more long-term note, Republican legislators who are crafting any bill in New Hampshire should always ask themselves how the bill can help to grow New Hampshire’s emaciated civil society and incentivize conservatives to move to the state. Any program of attracting conservatives to New Hampshire will have compounding returns, shifting the electorate while also recruiting the personnel needed to implement sound right-leaning policies.

Above all, this means attracting young conservative families from other New England states. Focusing on young families involves giving up the traditional New Hampshire Republican dream that retired, child-free Republicans from Massachusetts will populate the state. This imagined wave of conservative retirees, if it exists, will not staff our agencies, prosecutors’ offices, or school districts.

While there are several steps that conservatives can take until the personnel problem is fixed, at the end of the day, some bills will simply not work without conservative personnel to enforce them. Conservatives must learn that personnel is policy.