Admittedly, it sounds like the start of a joke: “So a presidential assassin, a pioneering automaker, and an Academy Award-winning actress walk into a bar …”

But it’s not.

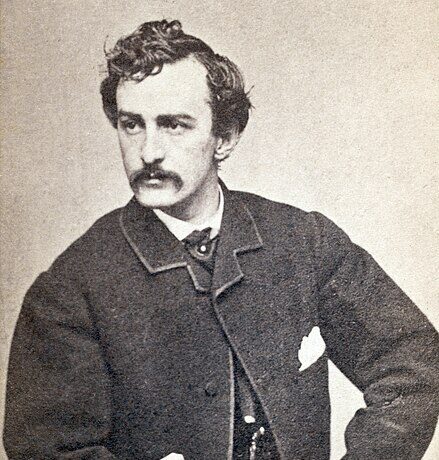

The (very) real story begins with John Wilkes Booth leaping out of the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre in Washington and into American history on the night of Good Friday 1865. Captured and killed at the end of a 12-day manhunt, he was quickly interred without the public glimpsing his remains. That was just fine with most Americans, who wanted to put the ugliness of Abraham Lincoln’s murder behind them.

But burying Booth secretly gave life to conspiracy theories that quickly spread across a still-divided nation. Whispers of, “You know, that wasn’t really Booth who was shot in that tobacco barn,” circulated for the next 50 years.

The paranoia peaked in 1907 with the publication of “The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth.”

Its author, Finis L. Bates, was born and raised on an antebellum plantation in Mississippi. Too young for the War Between the States, his family moved to Texas, where he became a lawyer. It was in the Lone Star State that Bates first heard a strange story.

As he explained in his 309-page book, Bates met a town character in Granbury, Texas, known for reciting long passages of Shakespeare from memory. (The Bard was Booth’s acting forte.) He went by the name John St. Helen, among others.

While ailing in the late 1870s, St. Helen supposedly told Bates, “My name is John Wilkes Booth, and I am the assassin of President Lincoln … notify my brother (the famous actor) Edwin Booth, of New York City.” St. Helen recovered and later skipped town, never to be seen in Granbury again.

Bates initially thought the story was a bunch of malarkey. But the more he pondered it, the more intrigued he became. In 1900, he wrote to the War Department, claiming the $100,000 reward offered in 1865 for Booth’s capture. (He didn’t get it.)

Then, in 1903, Bates was reading the newspaper when a photo caught his eye. Though he was now practicing law in Memphis, Tenn., the crazy story he’d heard 25 years earlier still fascinated him. Bates read that a man named David E. George had committed suicide in an Enid, Okla., hotel room and how, following a previous botched suicide attempt nine months earlier, had said, “I am the one who killed the best man who ever lived. I am J. Wilkes Booth.” The report was accompanied by a photo of George’s embalmed body.

Perhaps Bates recognized the face as John St. Helen. Some accounts claim the dying George had summoned Bates. Either way, the lawyer immediately hopped on a train and headed for Oklahoma.

As bizarre as things were up until then, they quickly turned surreal.

When nobody claimed the amply arsenic-embalmed body, the funeral director sat it in a chair in a window, eyes opened and holding a newspaper, as an attention-getter. Over eight years, 10,000 people gawked at the corpse. When the novelty wore off, and with nobody wanting it, the body wound up in the garage at Bates’ Memphis house.

This is where Henry Ford rolled into the story. The early auto giant stumbled into the quicksand of controversy when he was quoted in a 1916 Chicago newspaper article saying, “History is more or less bunk. It’s tradition. We don’t want tradition. We want to live in today, and the only history that’s worth a tinker’s damn is the history we make today.”

As a result, the man whose assembly lines were cranking out streams of Model T’s was forced into mass-producing damage control.

In 1919, Ford learned of Bates’ book and realized that verifying its claim that Booth had escaped would vindicate his “history is bunk” statement. So he set researchers looking into it. He even invited Bates to visit him in Michigan, whereupon Bates offered to sell him George’s corpse. When Ford’s fact-finders failed to substantiate most of the book’s allegations, Ford passed on the mummy.

Bates eventually rented it to a showman, who, in turn, rented it to touring carnivals as a freak show exhibit. At one point, outraged aging Union Civil War veterans threatened to hang the corpse. It bounced around from one increasingly seedy carnival to another and was last seen in the late 1970s.

Bates believed the Booth-St. Helen-George story until the day he died in 1923 at age 75.

He never met his granddaughter, who was born 25 years later. Meaning he also never saw the night in March 1991 when Kathy Bates won the Best Actress Academy Award for her role as the creepy nurse in the hit movie “Misery.”

Though at last word, no one has questioned her Oscar’s authenticity.