They say getting there is half the fun. But that wasn’t the case for one man over 175 years ago. In fact, his trip was anything but pleasant. However, the sweet reward he received at the end of his incredible journey more than made up for the hardship.

From the moment the first slaves arrived in the Virginia Colony in 1619, those in bondage began looking for a way out. Over the next 230 years, they devised many ways to escape their enslavement.

The simplest, most direct of all was to simply run away, of course. They fled by foot, often at night and heading due north, sometimes via hills and mountains whenever possible.

But that entailed the very real risk of capture and punishment.

Some used rivers and streams. Swamps provided another route because it was harder to track runaways in the murky water. (Though the danger from alligators and other threats was just as great to those in flight as it was for those trying to stop them.) A few daring souls in coastal communities even set out to sea on makeshift vessels they assembled from whatever materials they could find.

In time, a secret, informal network of safehouses and volunteers seeking to assist fleeing slaves was cobbled together. By 1840, it began being called the Underground Railroad. Its ranks grew considerably after Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850.

But Henry Brown tried a very different approach.

Born into slavery in Virginia, Brown eventually married and had two children. He was rented to work in a tobacco factory in Richmond. When his pregnant wife and children were sold to another owner in another state, Henry decided it was time to make his move.

He enlisted the help of two men, one a free African American and the other white. Together, and planning in coordination with an abolitionist group in Philadelphia, they devised an audaciously simple scheme.

It was set into motion one day in late March 1849. Henry intentionally poured sulfuric acid on his right hand, burning it to the bone. Though terribly painful, it provided a pretense for missing work.

Next, Henry crawled into a 3-by-2.67-by-2 feet wooden box labeled “Dry Goods.” Then, the lid was nailed shut behind him. The interior was covered with a coarse woolen fabric. Henry had only a handful of biscuits and the least amount of water he could get by with. A single tiny hole provided the only fresh air. The box was secured with leather straps.

A deeply religious man, Henry no doubt prayed as the box was dropped off at the office of Adam’s Express, the FedEx or UPS of its day. (The postal service only carried letters at the time; it didn’t begin delivering parcels until 1913). The company was chosen because of its reputation for efficient delivery and complete confidentiality.

The box departed Richmond on March 29 with Henry hidden inside. Delivery was made first by wagon, then railroad, followed by steamboat, a ferry, and railroad again, with a final wagon trip to Philly’s Adams Express office. The people who handled packages then apparently paid as close attention to them as they do today, for although the box was clearly marked “handle with care” and “this side up,” it was manhandled and placed upside down several times.

Henry didn’t dare make a sound. Discovery would carry swift and serious consequences. But he knew the risk was worth it. “If you have never been deprived of your liberty, as I was,” he later wrote in his autobiography, “you cannot believe the power of that hope of freedom.”

The drive from Richmond to Philadelphia today usually takes about four hours (providing I-95’s fickle traffic cooperates). Henry’s trip took 27 hours, which was considered rapid at that time.

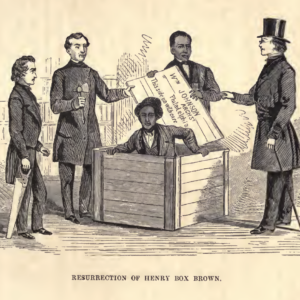

A group of local abolitionists was waiting at the shipping office. A crowbar pried off the lid, Henry sprang to his feet and said, “How do you do, gentlemen,” followed by singing a version of Psalm 40.

The only thing more incredible than the fact that the plan worked was there had been no difficulties. Henry’s wounded hand (and two very cramped knees) were the only injuries.

From that moment on, the newly freed man had a nickname: Henry “Box” Brown.

His journey received widespread news coverage. That displeased abolitionists because the leaked details of the operation prevented it from being used again.

And so, to the best of history’s knowledge, “Box” Brown was the only person who was ever shipped out of slavery.