What began as a cheerful Facebook post about homemade pickles has fermented into a political dust-up, complete with cease-and-desist letters, city hall warnings, and pushback from prickly state legislators.

Dan Mowery, a Manchester resident, is known for his homemade bread-and-butter pickles. “Not dill,” he insists. “My grandmother’s recipe — but I tweaked it.”

After posting online that he had “put up 18 quarts and 14 pints” of his tart creations, Mowery was flooded with requests from friends who wanted to buy a jar or two. He happily obliged, charging just enough to cover his costs.

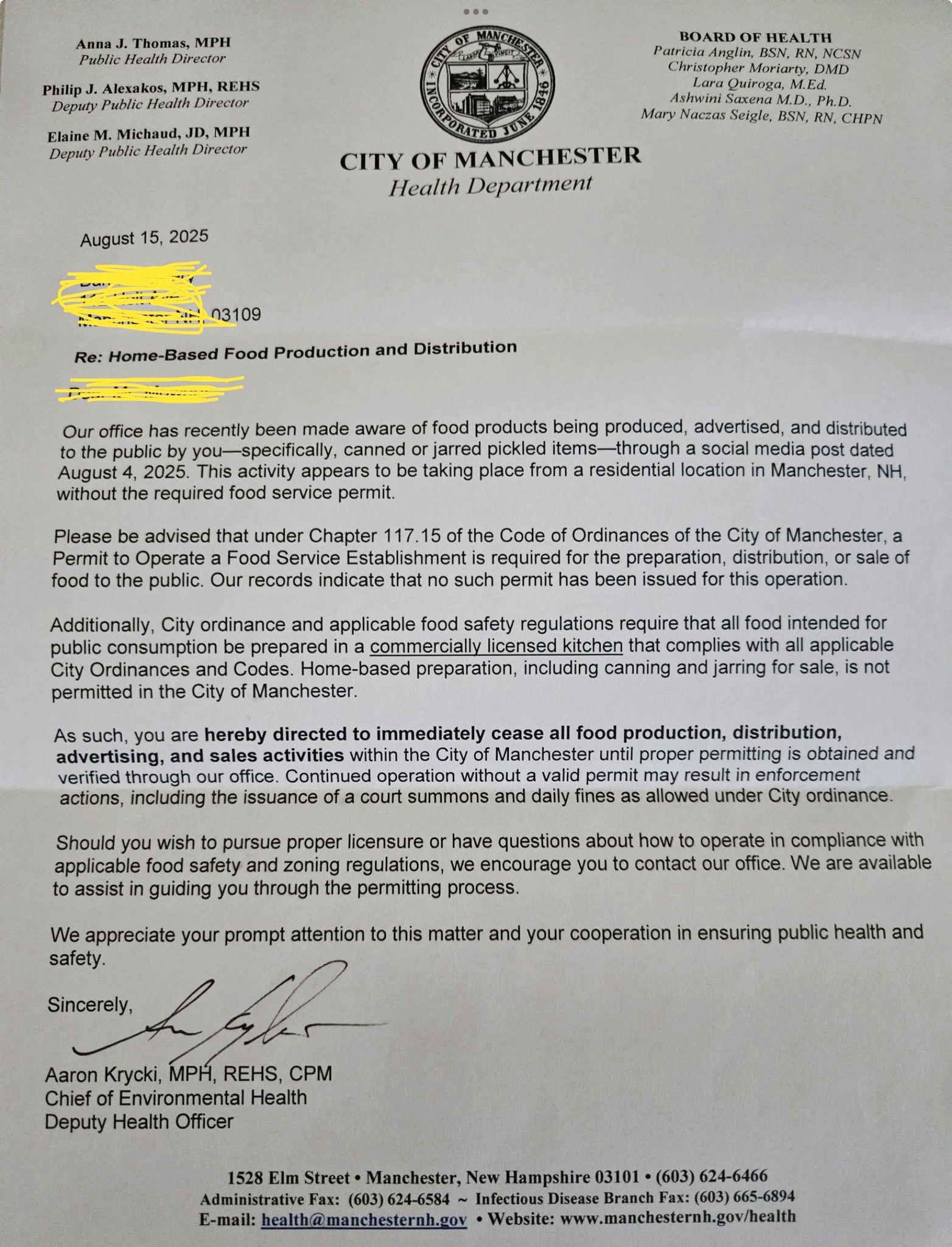

But word of the casual pickle sales reached Aaron Krycki, Manchester’s Chief of Environmental Health. Soon after, Mowery received a cease-and-desist letter warning that his side hustle could amount to a criminal offense.

“Our office has recently been made aware of food products being produced, advertised, and distributed to the public by you — specifically, canned or jarred pickled items — through a social media post dated Aug. 4, 2025,” Krycki wrote. “This activity appears to be taking place from a residential location… without the required food service permit.”

The letter warned that continued sales could result in fines, court summonses, or other enforcement actions.

When Alderman Joe Kelly Levasseur saw the letter, he couldn’t believe it.

“Dan’s got the pickles, but the government is full of baloney,” Levasseur quipped.

He posted the letter on Twitter/X, warning residents, “If you are going to jar some pickles and give some to your grandma or neighbor, don’t post about it on social media. You never know who’s going to snitch you out to the Manchester Health Department.”

Levasseur thought the post might “get a couple of likes.” Instead, it has been read more than 20,000 times.

Members of New Hampshire’s Libertarian and Free State communities quickly weighed in, insisting that state homestead kitchen laws exempted small-scale food sellers like Mowery. But Manchester Health Director Anna Thomas wasn’t buying it.

“State exemptions do not preempt municipal authority to enact local regulations,” she wrote in a pointed response. “In the city of Manchester… residential kitchen operations are not permitted unless they meet specific health and safety conditions.”

Levasseur fired back online: “NO PICKLING in MANCHESTER! The Municipality has 100 percent legal control over you jarring PICKLES!”

“The irony is that the same department that hands out needles to drug addicts says you are not allowed to sell unlicensed pickles,” Levasseur told NHJournal. “But heroin — no problem.”

Levasseur isn’t the only official jarred by the city’s reaction. State Sen. Tim Lang (R-Sanbornton) says lawmakers may need to step in.

“The state created the homestead food license exemption for a reason, and that reason wasn’t to let towns and cities get in the way,” Lang said. “I’ve added this topic to my list of bills to file in September to make our intent clearer and explicit.”

Meanwhile, Mowery remains under the obtrusive eye of city health officials.

“I’m hoping the resolution is the city will get out of this business and let people like me do what we do,” he said. “I’m not trying to make a profit. The jars cost money, the spices — I’m just covering costs.

“And I hope this doesn’t hurt churches or charities with bake sales,” Mowery added. “I don’t want them shut down because the city of Manchester wants to have its hands in everyone’s kitchen.”