A movement known as the Convention of States (COS) has been gaining traction across the country. The movement seeks to bring delegates from all 50 states to propose amendments to the Constitution by invoking Article V. Nineteen states have passed legislation approving such a convention, and an additional 21 have active bills in their legislatures.

While the movement’s goals are noble, its ends don’t justify the means.

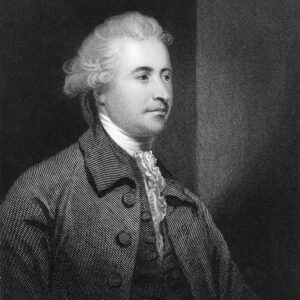

Fortunately, Edmund Burke’s brand of conservatism can lend some valuable insights on achieving similar goals, albeit in a pragmatic and piecemeal fashion.

Burke’s conservative philosophy can essentially be summed up in one sentence: all change is not change for the better; proceed with caution.

According to Burke, our approach to human affairs should be done with “mistrust” to both “a priori reasoning and revolution” (revolution meaning abruptness) and that we ought to put our trust in “experience and in the gradual improvement of tried and tested arrangements.” Pragmatism and incrementalism should reign supreme.

The COS and its unconventional approach are antithetical to Burkean conservatism. Traditional Burke conservatism prizes slow, gradual and step-by-step changes. The COS movement eyes the abrupt and expedient route, which could result in unforeseen consequences.

Conservatives are not stuck with the COS option. Today, 200 years after Burke’s death, his method remains a helpful guide to changing our cherished Constitution.

Our republic, with its democratic institutions of checks and balances, is, by its very nature, meant to be slow and deliberate. People often gripe and moan about how checks and balances result in nothing getting done, but they ensure prudent decisions. For a policy or amendment to become law, it should have to pass through the gauntlet of democratic guardrails.

This is especially true of a proposed amendment to the Constitution, given that it will affect all 330 million citizens. If friction arises, then the policy or amendment should go back to the drawing board: meaning more deliberation and further compromise. Careful consideration of such proposals guarantees that one side won’t get more than the other, which is especially important in today’s partisan political environment.

Changes will be gradual as opposed to sweeping.

Further, a tried-and-true Burkean avenue to amending the Constitution already exists. Article V, the article that allows for the calling of a convention, provides that an amendment to the Constitution can be made only if approved by two-thirds of both chambers of Congress and three-quarters of state legislatures.

Thirty-four states are needed to call a convention, but 38 states are needed to pass proposed amendments at the convention. These 38 states would represent the three-quarters of legislatures required, so the two-thirds of Congress needed is an added layer of deliberation and pragmatism that Burkean conservatism advocates.

Also of importance is today’s hyper-partisan era. If states called a constitutional convention today, delegates would push for their respective partisan desires. Proposed amendments should be indicative of moderation, not partisanship. Expedited and partisan measures do not align with traditional conservatism’s pragmatic and piecemeal ways.

At the end of the day, the COS movement has valid and legitimate reasons for wanting to invoke a constitutional convention. Unelected bureaucrats run amok in Washington, trashing our values and trampling our constitutional rights.

However, the movement’s desire to invoke Article V of the Constitution is the nuclear option, which should be done only in the case of a runaway government. For now, the Burkean path of deliberation and compromise leading to gradual and incremental change represents the best way forward.