When Cinde Warmington ran for governor in 2024, she released an energy plan calling for “net-zero emissions by 2040.” While it may sound extreme, Warmington’s proposal placed her squarely in the New England Democratic policy bell curve, alongside Govs. Maura Healey of Massachusetts and Janet Mills of Maine, who have also embraced “net-zero” goals.

They’ve made proposals, but they haven’t made progress.

When Granite Staters cranked up the heat during Monday’s snowstorm, the No. 1 source of their electricity wasn’t wind, solar, or even nuclear power.

It was oil.

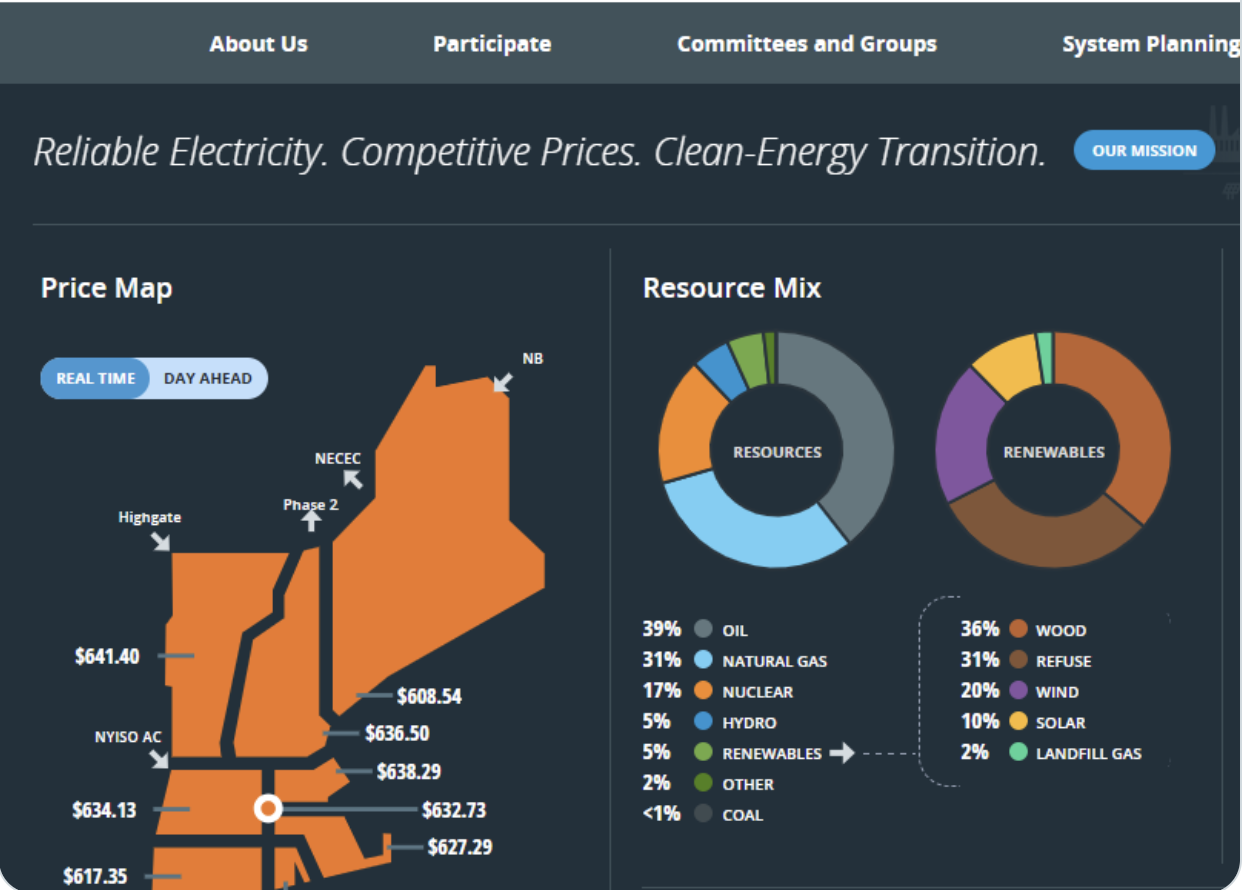

At times during the previous 48 hours, about 40 percent of the electricity on the New England grid came from burning oil, while another third came from natural gas. At the same time, just 1 percent came from wind, and about 0.5 percent came from solar.

At times during the previous 48 hours, about 40 percent of the electricity on the New England grid came from burning oil, while another third came from natural gas. At the same time, just 1 percent came from wind, and about 0.5 percent came from solar.

While climate activists may oppose the use of any fossil fuels, there is a major difference in carbon output between natural gas and oil. Used to heat homes, oil is about 40 percent more carbon-dense than natural gas. Used to generate electricity, oil produces roughly 150 percent more carbon than gas.

How did blue politics and green policy lead to the burning of so much black oil?

“You know why,” House Energy Committee Chair Michael Vose (R-Epping) responded when NHJournal asked. “Not enough peak-demand pipeline capacity. Generators refuse to purchase gas contracts. Renewables are almost useless on a day like Monday. So oil gets the call.”

The data backs Vose’s claim.

Despite sitting just a few hundred miles east of one of the world’s largest supplies of cheap natural gas, the six-state region remains an effective “energy island,” barricaded from affordable fuel and forced into a high-stakes balancing act to keep the lights on.

Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale region is awash in natural gas, trading for prices as low as $2.50 to $4 per million British thermal units. Yet during a January freeze, prices at the New England regional hub can skyrocket to $20 or $30.

That massive disparity — often resulting in New Englanders paying some of the highest electric rates in the country — is what economists call “artificial scarcity.” For more than a decade, attempts to build adequate pipelines across New York and Massachusetts to reach New England have been blocked by Democratic administrations.

As attorney general, Healey worked to block pipeline expansion in the Bay State, suing to stop development. Following court rulings and the subsequent cancellation of projects like Kinder Morgan’s Northeast Energy Direct (NED) and Spectra’s Access Northeast, Healey’s office issued statements applauding the decisions.

The result is a bottleneck. When heating demand peaks, existing pipelines reach capacity limits, and natural gas prices spike. As a result, ISO New England turns to oil.

“Because of restricted supply, oil is cheaper than natural gas right now,” said state Rep. Michael Harrington (R-Strafford). “Some of our power comes from dual-fuel plants that switch from natural gas to oil when oil is cheaper.”

Harrington, a former member of the state Public Utilities Commission, said oil is a precarious safety net.

“These plants only have a limited supply of oil. It costs money to buy and store oil just in case,” Harrington said. “If the weather stays cold for an extended period of time, many of these dual-fuel plants will run out of oil.”

Roughly 30 percent of New England’s power generation can shift to burning oil, relying on finite on-site storage that often holds just seven to 10 days of fuel.

The “energy island” syndrome isn’t limited to New England.

“Power plant outages surged along the eastern United States on Sunday as constricted natural gas supplies and frigid temperatures cut the electricity output of the region’s generation fleet,” Reuters reports.

“Power prices in grid operator PJM and the electric grids for New York and New England surged between $400 and $700 per megawatt-hour Sunday afternoon,” grid operators reported.

Those surging prices will be paid, one way or another, by ratepayers, energy policy experts say. As Energy Secretary Doug Burgum noted earlier this year, “Energy inflation is over 30 percent higher in blue states than red states, and it’s no secret why.”

The good news for Granite State ratepayers is that the “energy island” dynamic may be nearing its final days. In a significant shift this month, the federal government is moving to break state-level pipeline blockades.

Citing national energy security and recent court rulings limiting states’ ability to veto interstate infrastructure, developers refiled paperwork Jan. 8 to revive the stalled Constitution Pipeline. If built, it would connect Pennsylvania shale gas directly to New York and New England markets.

For now, however, New England remains caught between eras — aggressively building the grid of the future while anxiously clutching the oil tanks of the past, hoping the heat stays on until spring.

Something has to change, Vose said. If New England energy policy continues to disadvantage fossil fuels while demand continues to rise, “then we’ll face blackouts.”

Ironically, that’s another way to reach Warmington’s “net-zero” goal.