New Hampshire’s housing shortage has gotten so painful, it’s become part of political conversations from Manchester City Hall to Washington, D.C.

The lack of affordable housing is a hot issue in the Manchester mayor’s race, while Democratic candidate for president Rep. Dean Phillips says “affordability of housing” is one of the top concerns he’s hearing about on the Granite State campaign trail.

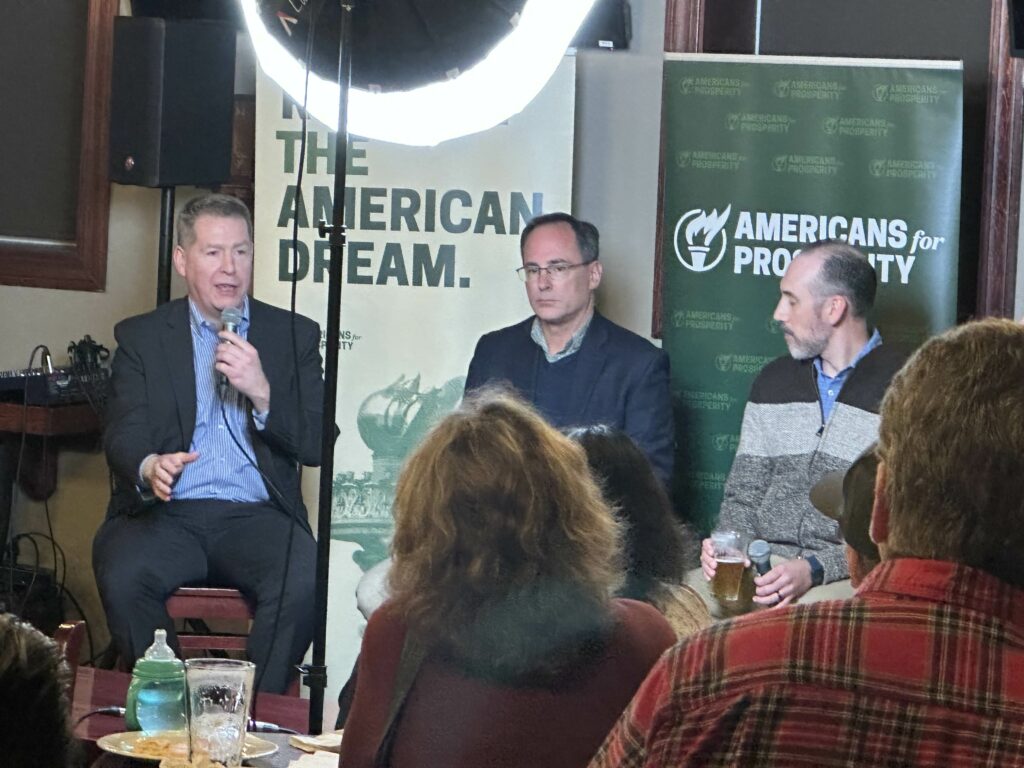

Which is one reason Americans for Prosperity-New Hampshire (AFP-NH) made housing policy the topic of its most recent Pints & Policy event at Murphy’s Taproom in Manchester.

The roundtable conversation was led by AFP-NH state director Greg Moore. Economist Adam Millsap, a senior fellow for Economic Opportunity Stand Together Trust, was one of the panelists, along with Rep. Joe Alexander (R-Goffstown), chair of the House Special Committee on Housing, and Drew Cline, president of the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy.

An August 2023 poll from the UNH Survey Center found Granite Staters named affordable housing the biggest problem facing New Hampshire. That same month, the New Hampshire Association of Realtors (NHAR) reported the housing affordability index fell to 59, the lowest number on record.

“We continue to see a lack of affordable housing in the state, and the affordability problem is directly tied to the inventory problem,” Ben Cushing, NHAR president, told NHJournal.

While the Pints & Policy conversation touched on a wide range of issues related to the Granite State’s lack of housing, Moore summarized the conversation with a simple question.

“Want to expand the housing supply in New Hampshire? Expand property rights,” Moore said. “Zoning and planning exist to limit people’s property rights. While there are some good things that come from that, such as not allowing a junkyard next to a town well, many of these boards simply engage in central planning exercises at the expense of landowners’ rights. This dramatically limits the supply of housing to meet demand and it’s why we have a housing crisis in New Hampshire.”

Millsap repeatedly referenced minimum lot size requirements as an obstacle to new housing in the state.

“Here in New Hampshire, you’ve got three-acre minimum lot sizes in some places,” Millsap said. “It’s hard to put small homes on a lot of land. There are also height requirements, density requirements, environmental reviews — a list of things that just make it take too long and too expensive to build houses.”

Millsap rejects the idea that increasing density means destroying community culture or overcrowded neighborhoods.

“When some people hear ‘high density,” they think Manhattan or Hong Kong. But you can have a lot of density and still have a quaint, single-family neighborhood. Think about the neighborhoods some people value the most, like Main Street neighborhoods in smaller towns that are very walkable. You don’t have to turn into Manhattan to have more density, more supply and more homeowners.”

AFP-NH hosts a Policy & Pints event on housing policy at Murphy’s Taproom in Manchester, NH

Not all of the attendees agreed with the premise of the AFP-NH event.

“The word ‘crisis’ is overutilized and ‘housing crisis’ is one example,” said Rep. Len Turcotte (R-Barrington). “We are in a typical, cyclical real estate situation — definitely not a ‘crisis.’”

Asked about surveys showing young Granite Staters in particular are complaining about the lack of affordable housing, Turcotte blames it on skewed expectations.

“When I was a young person, I didn’t have expectations that right out of school I could afford a two or three-bedroom house,” Turcotte said, “I lived in a three-bedroom condo with five people, so I could afford a home when I hit my 30s.”

State leaders like Gov. Chris Sununu have made it clear that keeping New Hampshire growing — even as other New England states lose population — is going to be difficult without more housing supply. both for workers who move here and young workers who want to stay here.

Rep. Alexander touted the value of the state’s new land use docket in superior court, which will help speed up the process of adjudicating disputes over development, which currently take three years to resolve. “Three years is too long,” Alexander said. “If I were a developer, I would walk away. I’d say, ‘It’s not worth it to me, it’s too much time and money.’”

“We need to identify that part of the problem is the slow approval process [at the local level],” Alexander said.

As for the idea that housing should wait until the local government builds infrastructure like roads, sewer and water systems, Millsap said that’s the wrong way to think about it.

“If the government can’t build the roads and sewers that we need, then what good are they? It’s the government’s job to keep up with the housing demand. If people want to live there, it’s the government’s job to make it possible. That’s what we pay taxes for.”