It happens every so many years. Activists in one of the major political parties make noise about moving their first presidential primary, the ballot-casting hullabaloo that sets the whole nominating process in motion, to another state. It mostly comes from the Democratic camp though GOP griping, while less common, does happen from time to time.

But this time is different. Because in 2022, the Democratic National Committee appears to be quite seriously considering undoing the electoral triumvirate—Iowa’s Caucuses, New Hampshire’s inaugural First In the Nation primary, and South Carolina’s First in the South primary—that has maintained an uneasy partisan peace for a generation.

Let us set aside the current debate and consider this: How did we get here in the first place? More specifically, how did the Granite State wind up going first?

You must first go back to the early days of the 20th century. A wave of progressive reforms was sweeping the country just then. (Though it is important to note the people who self-identified as “progressives” at that time were a far cry from the ultra-liberals who style themselves as such today.)

They wanted to change many things about government and politics. Ranking high on their to-do list was changing the way presidential nominees were selected. At the time, the nomination was decided by party bosses who wheeled and dealed in so-called “smoke-filled rooms.” Detractors said the far-from-transparent procedure left Americans straddled with less than spectacular presidents such as Harding, Buchanan, and Taft. Though in fairness, that same process also gave us Lincoln, Wilson, and both Roosevelts. It was hit or miss.

Florida got the reform ball rolling in 1901 with an early primary forerunner. Wisconsin followed in 1905, becoming the first state to let voters select national convention delegates, similar to the way Americans choose the electors who ultimately elect the president. The movement began picking up steam. New Hampshire jumped on the bandwagon in 1913; when the next presidential election was held in 1916, 26 of the then-48 states directly elected convention delegates, held presidential preference primaries or did both.

And New Hampshire wasn’t the first in the nation that year, either. It came a week after Indiana’s and fell on the same day in May that Minnesota held its primary.

But something interesting happened in that 1916 contest. It was a colossal flop. Voters around the country gave a collective yawn and skipped the primary election. Turnout was so low, in fact, states considered it a failed experiment and scrubbed their primary. One by one, they began falling by the political wayside.

New Hampshire bucked that trend and clung to its primary, but with one important change. State lawmakers, driven by traditional Yankee stinginess even more then than now, moved the date way up to coincide with Town Meeting Day, the second Tuesday in March. (Why pay for two election days when one would suffice?)

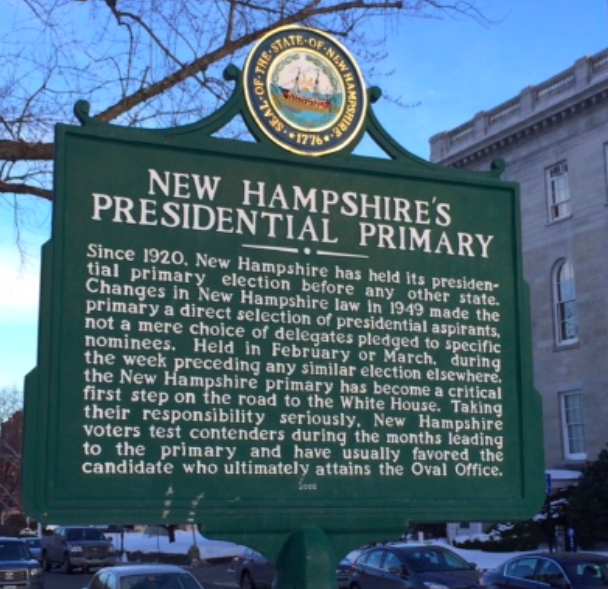

Which was why New Hampshire led the nation in primary voting starting in 1920 and continued to do so for the next 100 years. Though Granite Staters were still only selecting convention delegates, and there was no guarantee which candidate those delegates would support at the national nominating convention that summer.

And so it remained … until state House Speaker Richard Upton decided to shake things up and make it interesting. He led the charge in 1949 to put candidates’ names on the ballot. Voters still selected convention delegates. But starting in 1952, they also voted for the individuals they wanted to be their party’s nominee.

There was much political drama that season, with Dwight Eisenhower and Robert Taft slugging it out on the Republican side while Adlai Stevenson, Estes Kefauver, and other Democrats also fought it out on theirs. (Ike and Stevenson eventually won, but the way.)

That contest put New Hampshire’s primary on the political map and placed the FITN title on its head. It became such a cherished badge of honor that in 1975 the legislature codified its sacred status by passing a law requiring the secretary of state to set the presidential primary date earlier than any other state’s similar contest—as many as seven days earlier, just to be sure.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Time and space do not permit a complete consideration of the countless dreams that came true and hopes that were crashed on primary night once the results were known, nor the many tweaks and update the process itself underwent along the way.

What matters is that thanks to being home to the FITN primary, a very small state has had a big impact on the nation’s political destiny for 75 years. Instead of bowing to the wishes of large population states like California, New York, Illinois, and others, campaigns at the highest strata of national politics must first appeal to single moms and small business owners, to military veterans and retirees in a little state they otherwise would likely take for granted.

A casual reading of “The Federalist Papers” leaves one feeling the Founding Fathers would be very proud to know that.